This article does NOT contain Spoilers.

When I was a teenager and falling in love with movies which went beyond Disney fare and special-effect-laden extravaganzas, one of my touchstones was a frayed hardcover from 1966 in my high school library. Stanley Kauffmann’s A World on Film opened my eyes, through its plethora of reviews of films I’d never even heard of, to how much potential those who work in the medium can achieve. There are still passages committed to my memory, among them his August 29, 1960 piece on Jack Cardiff’s film of Sons and Lovers which created a further obsession of mine: the question of adaptation.

Kauffmann spends the first half of the review pondering why adaptations in general almost always fall short of their source material. His conclusion is that people who have read the book will feel what is lacking, and people who haven’t find adaptations, in his words, “frequently unsatisfactory…for the screenwriters are to some degree hobbled by the book and cannot follow their best cinematic instincts.” What Kauffmann meant by this is that film and literature work in two different ways. Literature, fiction or non-fiction, is an interior art, able to plumb emotional and psychological depths and leaving the look of setting, character, and action to the reader’s imagination. Film is an exterior art of explicit visuals which has developed its own storytelling conventions and means of pacing. Often, the core elements of a great novel—characters, themes, basic plot—would make a great movie if they were used as the basis for a new telling of the story, but adapters so often get hung up on an overly respectful conception of fidelity to the source that instead they produce what Kauffmann describes as “illustrated scenes from a novel.” This is a path which produces no guarantee of success at best and failure at worst.

For example, Sons and Lovers, which ended up a reasonable hit and garnered multiple Oscar nominations, was produced by Jerry Wald, who in the late fifties masterminded a string of films which raked in profits and considerable reviews and awards attention. Wald’s tactic was to create adaptations of well-known novels with reputations for being “adult” and put them on the big screen with enough suggestions of sex and other unmentionables to stay within the bounds of the Hays Code. Besides Sons and Lovers, Wald had smashes with Peyton Place and the William Faulkner-based The Long, Hot Summer, although The Sound and the Fury was not quite as popular.

Did Faulkner know he was breaking the unwritten commandment? And that Yul Brynner with a hairpiece would play Jason?

Each of these Wald films had one other thing in common: his writers never got inventive with the material for cinematic purposes. There is nothing which stands out in these movies except for what can now be judged as overly melodramatic acting. They are Kauffmann’s illustrated scenes writ large.

On the other hand, The Great Gatsby is one of the best novels ever written, and there has never been a successful film version despite multiple attempts and probably never will be. A movie can reproduce the Jazz Age atmosphere to the last authentic detail, find the perfect actors, use as much of Nick’s narration as they please—but can never recreate the rhythm and emphases in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s writing or create all that he leaves unspoken and implicit. When we read Gatsby and so many other great novels, the impression is created that we are seeing only part of a character as opposed to a whole, and that so much backstory and thought, be it deliberate or instinctual, factors into their decisions and every sentence they speak. It is unraveling these complexities, interpreting the text for ourselves, which makes reading so special. Film, because it is explicit and active, even in the most artistic works of Bergman and Antonioni, often ignores these aspects or tries to depict them—a catch-22 because they were never meant to be depicted, but without them, the story doesn’t work as well. Thus, we arrive at the unsatisfactory state proposed by Kauffmann.

Yet filmmakers press on with adaptations, trying to find the right means to get both what is and is not said onto the screen. And in my years of watching movies based on books, what I have found is that every adaptation stands and falls by a methodology unique to each individual film, and based on an individual decision by each adapter: determining what the story’s most important parts are for expressing the central themes they want emphasized, and using these actions and themes as the guiding principle in selecting what stays in and is cut out.

For example, most film and television versions of Anna Karenina almost ignore half the novel, overlooking the Levin/Kitty portion to concentrate on Anna’s affair with Vronsky, which admittedly is more racy and dramatic and offers a simple morality tale. But Tolstoy’s emphasis in the novel was to continually contrast Anna and Levin as people searching for happiness along very different paths. The story of his success enriches that of her failure, but Levin’s part of the story is more introspective, less visual. Te most exciting moments are solitary hunts and a protracted death scene: not the stuff of what memorable movies are usually made. But the point is a movie could be made which marginalized Anna/Vronsky in favor of Levin’s courtship of Kitty and be equally faithful to the source, just emphasizing different themes. The ideal adaptation would follow Tolstoy’s division as closely as possible.

One series of movies which pulled this off successfully was The Lord of the Rings. Peter Jackson decided (at least from my observation of what was left in and what fell by the wayside) that the story was really about two people. Frodo, who loves his home more than anything, must leave it and cross all Middle-Earth to destroy the Ring, and Aragorn, who wants nothing more than a quiet life with Arwen, but must take his rightful place as the King and lead the other men into a new and greater age. They take sometimes spectacular action to fulfill selfless destinies, an interpretation I am sure would have pleased the very religious Tolkien. Once Jackson had his focus, so many pages of the book got shredded. Tolkien’s songs, tales of Elvish lore, interminable documenting of settings and every step taken on every stage of every journey, all of this could be dismissed as extraneous or reduced to a shot of them walking across a landscape, or centering the dialogue as it directly related to the two main strands of narrative. In doing this so successfully, Jackson and his team had help from Tolkien himself, who kept all three books within his singular but unvarying tone of learned storyteller. The story of The Lord of the Rings is consistent. It never suddenly becomes a comic romp or a bodice-ripper or more suspenseful than the natural “How are they going to make it?” curiosity.

But what if it isn’t clear what the story is or what the central themes are? Don Quixote has been self-sabotaging film versions since a time long before Terry Gilliam and Johnny Depp gave their try. The trouble with Quixote is that there is a central idea, but the magic and genius lie in the episodes which branch off that idea and substitute for an actual plot: the people Don Quixote encounters and whose love lives he integrates himself into, Sancho’s governorship, the meta-textuality. Even Dulcinea is not a major character in the book, no matter what endless listens of “The Impossible Dream” make us believe. An adapter has to decide which parts to leave in alongside the tilting at windmills and which parts to eliminate, but by the above guidelines, most of what captivates us in Quixote is tangential to the crazy old man and resourceful, learning sidekick. Integrating those parts into a cinematic story becomes a matter of randomness and personal taste as to what episodes will remain. There could be an infinite number of Don Quixote movies, once we factor in considerations such as deciding if Quixote is truly insane or not. No wonder adapters throw in the towel so often!

But this method has worked for other movies. Along with The Lord of the Rings, one of my favorite cinematic adaptations is David Lean’s 1946 Great Expectations. The film captures the inimitable tone and atmosphere of Charles Dickens, mostly because Lean didn’t try to cram a shorthand version of every plot strand and character into the two hour running time. He engaged in the same randomness which would enter a Don Quixote adaptation, selecting the scenes he felt were absolutely needed and should be given in full richness, and then finding the most efficient and Dickensian ways to transition between the scenes and progress from first to last chapter. And it was easy for Lean to do this because Dickens, unlike Cervantes, provided a main plot with signposts for points A, B, C, up to Z.

Now, recently, innovations in technologies and techniques have led Hollywood to a new source material for adaptation which at first glance seemed to offer a chance for fidelity and satisfaction on levels too rarely achieved. Moreover, it was source material which in its nature consisted of clearly demarcated scenes, thus allowing for an easier breaking down and intelligibility. That source is graphic narrative: everything from the classic DC and Marvel superhero comics to more ambitious novels such as Ghost World and Watchmen. The combination of words and pictures, the interior and the exterior, suggested that all one needed to do for a film version was add motion and actual voices, because all of the scenes were in place and obviously defined; I still remember how much was made of Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller trying to recreate every single panel of Sin City. But the same plague of questions keeps arising. Even with demarcated scenes, what do you cut out to fit the film into a reasonable running time and a rating appropriate for your audience? How do you portray the richness of the characters’ interior lives which the author describes as well as the exterior action? And is it possible to recreate the tone and style and the literary touches which won the book an audience in the first place?

To meditate on these questions a little more and see if any answers can be arrived at, I offer a test case.

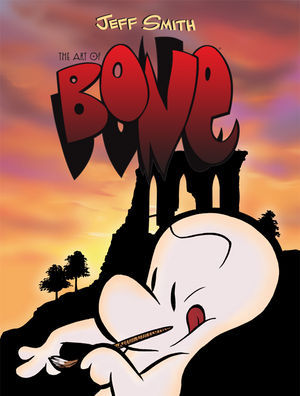

At the beginning of this year, Warner Bros. and their partner animation studio Animal Logic announced an adaptation of one of the most acclaimed comic books of the past two decades: Jeff Smith’s Bone. Though naming a writer (Patrick Sean Smith) and a director (PJ Hogan), the press release said nothing about whether it would be one film or a series as had been rumored. And it did not mention Smith’s earlier attempt in the early 2000s, which so nearly came to fruition, to produce a film with Nickelodeon-Paramount.

Unpacking the above paragraph starts with, appropriately enough, an implicit idea, namely that there must be something special in Bone that has prompted two major studios to spend fifteen years developing a film. And make no mistake, Bone is special.

It is a high fantasy tale which ranks with The Lord of the Rings and A Song of Ice and Fire as a pinnacle of the genre, a sweeping saga of quests, magic, and the fate of the world hanging in the balance; a world, it should be added, thoroughly built in terms of geography, culture, and social and political systems. More importantly, Bone never flags. It is perfectly constructed to provoke the highest level of suspense, its pay-offs always justify the set-ups, and it contains some of the most amazing set pieces in comics history, including the Crown of Horns volume which closes it out. The complete story runs for 1,332 pages, and when it’s over there may well be an irresistible urge to turn back to page 1 and start again.

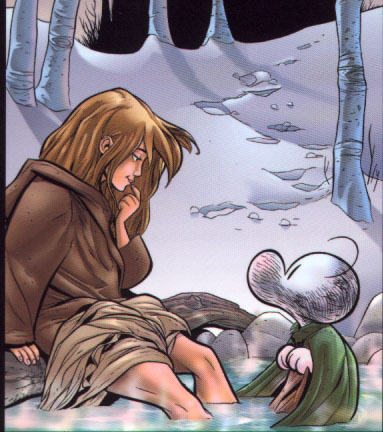

But not for the main story alone. Bone‘s two protagonists live out one of the sweetest and most endearing love stories in probably any literary field but certainly within comics. Fone Bone, is the straightforward, big-hearted young, um, something who loves reading Moby-Dick and, in the fantasy tradition, simply wants to get home, to Boneville, where all the other Bones live. But he puts this goal aside to, more in the style of Don Quixote, do all he can for Thorn Ravenstar, the beautiful girl who tends cows with her grandmother in the forest–and who might be the key to saving the world. Thorn never returns Fone Bone’s romantic feelings, but over the story they learn, grow, and change together along a very distinct path, a textbook of character development, and by the end have forged a platonic love more memorable than most Hollywood passions.

Bone further happens to be a brilliant comedy. The opening two volumes, Out From Boneville and The Great Cow Race, are played almost strictly for laughs, and throughout the story Smith always breaks up the encroaching darkness and more stolid themes with humor, usually from Fone’s cousins, the eternally-conniving Phoney and the brainless but loyal Smiley, who could have stepped out of the greatest 1930s screwball movies.

And… yes, there is another and… Smith adds layers of philosophy. Beyond the mythic hero’s journey undertone, a major element of the story is the Valley’s religion of accepting and interpreting dreams, practices which become more and more important by the final volumes. Bone ends up treating concepts such as faith (Fone and Thorn both struggle with this), morality (which is discussed many times, especially in the fifth volume when Fone confronts Roque Ja), and perception and consciousness…as dream and reality merge into a whole where telling the two apart becomes the most important thing of all. These concepts become matters of serious debate and subtle dialogue, treated with a very adult inquisitiveness and respect.

Oh, and Bone was also written as an all-ages book, with the Scholastic reprints of the nine individual volumes being among the publisher’s biggest sellers.

It is a testament to Smith’s artistry that these disparate factors all merged into a coherent and more than satisfying whole, and the desire for a film version of such a superbly written property becomes very understandable. Done right, Bone could be a wondrous motion picture on the scale of LOTR or Star Wars. However, the same qualities which inspired devotion and acclaim also make it a very troublesome work for adaptation.

Obviously, all 1,332 pages cannot stay in even if the film was made as a trilogy, but the changes to the story made by slicing things out here and there could potentially be dangerous. For Bone falls into a netherworld in the gaps between the books I discussed above. There is a clear main story: Fone Bone and Thorn unraveling the mystery of her past as they make their way towards a confrontation with the Lord of the Locusts. But the side stories involving Phoney’s running attempts to outwit Lucius and scam the people, Smiley’s unexpected friendship, and the midpoint interlude on the Eastern Border, all of which may at first seem tangential, end up being of importance.

To compound the difficulty, these side stories don’t occupy their own neat little corners of the narrative but are fully interwoven with the main story. Even though Smith was publishing Bone as single issues, he never thought things like, “hmmm, maybe I should stick everything about the Cow Race in one issue, then get back to Fone Bone and Thorn’s dreams!” Even in the last two volumes, when everything is marching towards an unstoppable climax, Phoney is operating a crackpot scheme to con his way into finding a massive treasure under the city, and the running gag involving quiche reaches its escalation. This is not cinematic storytelling, but it is great storytelling. Again, Smith made this a multi-generational story by never tipping the content too far to one side. He let little scary moments happen early on and made sure to brighten things up even when every character is engaged in violent struggle.

That may be the paramount issue. What gets cut out would affect the tone of the movie and might easily categorize Bone as some specific genre. No matter which tone gets chosen, so much which makes the story work will be lost.

Treating Bone as an epic quest adventure runs the risk of both eliminating much of the humor and reducing the character development. For it isn’t only that the comedy scenes lighten the mood. They also, in their pauses from the increasing action, give the characters room to stretch out, talk, and bring out different nuances of themselves. Their reactions to Phoney’s plans, for instance, reveal Fone Bone’s loyalty to his cousins and Thorn’s accepting but principled morality in ways the chases and fights never do. Readers fall in love with the characters in the lighter moments, and thus care about them more. Remove the humor, and Bone’s uniqueness among epic fantasy is reduced.

But emphasize the humor, and the outlandish slapstick hijinks, already goofier than usual thanks to the design of the Bones, could too easily dominate the story. Bone is a giant hit with children, but while there is a certain pleasure in watching Fone, Thorn, and Gran’ma Ben trying to keep Phoney under control while Smiley cracks wise, such focus would detract from the main plot, and the serious debates on morals, and the explanations of the Dreaming and the Ghost Circles, none of which have anything witty about them and push the book into thematics of warfare and death.

By now, good readers should be quibbling with my scenarios up above due to their all-or-nothing nature. A dedicated filmmaking team should be able to strike the right balance between the serious and the funny. This is a reasonable assumption, except for one key detail. In the one previous moment when Bone came seriously close to being a film, on a project with very active input from Jeff Smith, such an all-or-nothing scenario was the case.

As Smith described the Nickelodeon-Paramount movie he wrote and consulted on for two years, the plan was to adapt only the first two volumes and tie off the story with the first conflict against the Rat Creatures. It would have set up a sequel, but also could have been a standalone film. While not aggressively aimed at children, the first two volumes are the most child-friendly before the escalation of Eyes of the Storm. But Smith was so committed to recapturing the tone of the original that the picture only fell through after he objected to Nickelodeon’s insistence on incorporating new elements which would have made Bone more aggressively a kids’ movie, including having the clearly adult Bones played by elementary-aged boys, giving Fone Bone magic gloves that make things grow (and…how is he going to use these?), and creating a soundtrack with a still tween-idol (it was 2000) Britney Spears on vocals.

We can be thankful this movie never got made.

But in hoping that the new Bone film will be a more faithful reproduction, fans should set their optimism at a low level. Smith probably sanctified the aborted Nickelodeon project, and will probably sanctify whatever Hogan and Smith create, because deep down he knew that there was an inescapable scenario in the adaptation process. Bone is a work of delicate but achieved balance, and for every scene or plot point which gets eliminated, the balance tips. It is possible to maintain the balance through even-handed cutting… yet that would create a final problem which was almost unknown when Kauffmann wrote about Sons and Lovers.

In the days when Jerry Wald was producing his hits, films were still being made under the Hays Code for consumption by everyone in the country regardless of age. Marketing was creative and certainly aggressive, but not on the scale of today, when the ratings system, research into various audiences, and the multiplex have given a wider range of choice to filmgoers and more and varied films in cinemas. And with budgets on the increase year after year, studios want to know they are investing in a movie they can sell, a movie with a target audience and the means to make that audience aware of the picture. The recent debacle with John Carter is a demonstration of the risks undertaken involving giant productions: the movie was confusingly marketed (Who was this guy if you had never read the Burroughs novels? And what were those creatures?), never found an audience, and collapsed. In contrast, the people who just pumped $200 million into The Avengers in a single weekend, and a few years ago made Avatar a billion-dollar enterprise, in both cases had a strong idea of what the movie was and were given sufficient information about what to expect to entice them into the theater. Their studios knew they could reach a mass audience with strong reminders of familiar characters or an ambitious epic story with clear characters and technological innovation.

Bone is going to be a big-budget proposition. When marketing executives and public relations groups are brought in, they will be asked to sell a property which for all its success is not well-known to the general public and has a tone which is

A) philosophical, sometimes very dark, and full of unflinchingly violent action

B) has lovable central figures in the cartoony Bones and the gorgeous Thorn, a character as tough and resourceful as Katniss Everdeen.

Maybe this is an unfair misjudgment of modern Hollywood, but I would guess that the most likely result of an analysis would be that the above combination would be too much of a mess to market, and the best return on the investment would come from favoring B over A in adaptation. Because if the characters can’t change, and the characters appeal more to children and teenagers, the story can be altered to make it more of the sort of film Nickelodeon would have made.

The implications of this choice are felt even more because Warner Bros. has not commented on if one or several films will be made. If Bone was adapted in the same way they handled Harry Potter, a growing audience could follow from the joke-filled early sections to the more difficult and adult final parts over several years. But Harry Potter was a sure bet for the studio, a proven phenomenon, and greenlighting more than three Bone movies has probably never been in the cards. Hollywood as a proven fascination with trilogies, and a Bone trilogy could work. Smith himself divided the nine volumes into three equal parts reflecting the Valley’s changing seasons, with 1-3 serving as an introduction, 4-6 introducing the main conflict and deepening the characters, and 7-9 moving at a breakneck pace with battles, magic, and metaphysics. There might be enough space for the audience to mature with the story. However, most trilogies are contingent on the success of the first film, and as has been stated, the first part of Bone is so comic and appealing that a demand could be made for the further films to follow suit if it’s a hit, or have that be the only Bone movies would get if it’s a flop, a misrepresentation.

And if done as only one film…how? Not even four hours would be enough to get the full story in without major shorthand and elimination. A single Bone would almost certainly hew close to Nickelodeon’s attempt, latching on to the most definable audience and losing much of what made the book special.

There is hope in the choice of writer and director. PJ Hogan has achieved commercial and critical acclaim in the realms of fantasy (Peter Pan) and intelligent comedy (My Best Friend’s Wedding), while Patrick Sean Smith successfully blended humor and serious drama on his TV show Greek. These are filmmakers used to working in between set categories and striking tonal balances, and they might be able to do the same for Bone.

Yet because of all which has previously been written, there are no clear answers on how a Bone movie could recreate the unique mood and style of the comic books without a degree of faithfulness beyond reasonable hopes. And if this article has dwelled at length on its case study, it has done so to delve deeper into the inherent difficulty of literary adaptation, a process which itself has no steadfast rules and provides precious little intelligible reasons for its success, as both travesties and aggressively faithful retellings have been hits at the box office, the one lingua Franca everyone accepts in what is ultimately a business. That common goal, to be successful, is why adaptations are produced in quantity year after year…studios would rather take a chance on a story even mildly familiar to people than an original idea with untested coffer-filling ability. Hence, all those years ago, Jerry Wald briefly became an iconic symbol of Hollywood success.

But adaptations do not have to be Jerry Wald models of watered-down illustrated summary of a book. Bone could end up like that, or it could be a reasonably faithful children’s movie which recreates most of the story and dialogue while missing the spirit, or it could be a carefully made masterpiece which may or may not reach its audience. We will never know until the curtain rises on the night, if that night ever comes, of the premiere. And that day will be awaited with this worse uncertainty of quality.

However, the final thought of my meditation is this. Unless the signs all point to a total disaster, people WILL await the Bone movie, people who loved the book so. Because the true secret to adaptation may lie not in the change in how the story is told but I the change in how the story is experienced. Reading is a solitary act, for the most part, but film is one of the great arts of the public, a shared event on a giant scale. And psychologically, when we love something, we want to share it with others, clue them into why a story, a character, an idea means so much to us. And even the slimmest chance that an adaptation could pull it off through some great alchemy keeps us in a state of wanting.

Major source for information outside the comic itself: http://www.aintitcool.com/node/15592