As this Oscar season has rolled on, there’s been a semi-contentious debate amongst many of those on staff here at the Addison Recorder. This is nothing new to the website (ask Alex and/or myself about the merits of baseball if you have an afternoon that you absolutely have nothing better to waste it on), and is one of the benefits of working on a culture blog: everyone is sure to have an opinion. One of the arguments this year has been the relative merit of performances in regards to a film’s whole. Some of us reside in a camp that appreciates good acting on its own as a way of validation for a film, while others believe that outstanding performances are useless if the film has nothing to say or is nothing more than a rote recitation of familiar tropes. The film that has most come under fire is the biopic, a telling of a single character’s life story that often has a fairly simplistic underlying message. More often than not, these are films that are highly praised for their lead performances come Oscar-time, but seldom have a lasting impact upon popular culture. (Think Jamie Foxx in Ray, or Joaquin Phoenix in Walk the Line, a remake of Ray with white people.)

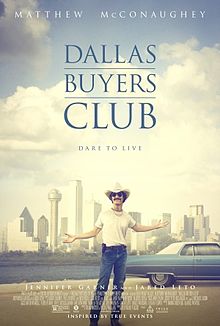

This year is no exception to bringing forth another film to add to the list. Dallas Buyers Club is a movie that has spent several years getting tossed around Hollywood in a nonstop quest for funding, taking shape in the early 90’s with Woody Harrelson attached to the lead role of Ron Woodruff. Over the years, actors such as Brad Pitt and Ryan Gosling have been tied to the part. It wasn’t until Matthew McConaughey signed on that the film gained any real traction, debuting last year to universal acclaim.

As stories go, the film doesn’t offer anything terribly new. Based on a true story, it tells the story of Ron Woodruff, a homophobic Texan electrician/pseudo bull-rider (a liberty taken by the film) who contracts HIV through unprotected sex and comes down with AIDS. Forced to confront his own mortality, he goes to great lengths to obtain treatments for the disease. When he discovers a treatment that will prolong his life, the opportunistic Woodruff realizes he can make a quick buck by selling memberships to the “Dallas Buyers Club” to those stricken with AIDS; a monthly fee of $400 entitles you all the drugs you need to survive. As the film goes along, Woodruff slowly confronts his own homophobia as he battles with the FDA to maintain some semblance of agency over his drug treatments. While there is obviously no happy ending to a film about a man with a terminal illness, the film musters up a moral victory, with Woodruff finally accepting those whom he has spent much of the movie milking for their money.

As far as stories go, the film (as I’ve said before) offers nothing new. It doesn’t overtly play to the heart strings, and the dialogue at times feels like a beating over the head with all the subtlety of “THIS IS IMPORTANT AND RELEVANT, GOD DAMN IT, AIDS IS BAD”. It wears its politics on its sleeve (the villain of the piece is the “evil” FDA director who seems to be going out of his way to screw over Woodruff solely to support “big pharma”) and has an derivative aesthetic that drips with the influence of 1970’s statement movies.

The real thing to talk about in the movie (possibly the only thing) is the quality of the acting. Every year, we as audience members are treated to fine showcases of acting come Oscar season, and in that respect, Dallas Buyers Club goes over the top with two of the finest lead performances of the year. (Well, lead and supporting, but we’ll get there.)

Let’s start with McConaughey. Long derided as the star of romantic comedy drivel who relied on his own personal charm and charisma to carry himself through movies, his career has taken a sharp turn in recent years towards quality fare. With strong performances in Magic Mike, The Lincoln Lawyer, Killer Joe, and Mud, the narrative of McConaughey seems to be reaching its natural climax with his work in Dallas Buyers Club. Having now seen the movie, it’s fair to say that he’s put his work in and stands at the head of his craft. His natural charm is still evident (Woodruff’s sister apparently said that the actor’s charisma sold her on his being cast because it so strongly resembled her brother’s natural way with others) but here it’s been honed, focused, used as a tool by Woodruff to get whatever he needs/wants at the moment. Much has been stated elsewhere about the physical effort that McConaughey went through to play the part (he lost over 50 lbs, and it’s clearly evident in every skeletal inch of his gaunt frame), so I won’t dwell on that here; in a way, such physical self-torment to me strikes as an overly indulgent and dangerous message – only by pushing my body to the limits can I achieve this performance. However, it’s safe to say that McConaughey becomes Woodruff both physically and emotionally. His most devastating moment is when he’s reached a low point and is staggering around in traffic, literally dazed and confused (pun semi-intended) after the ravages of the disease have taken a toll on his body. If McConaughey wins the Oscar for Best Actor, it’s hard to say that he hasn’t earned it. (Deserved is another topic – I still stand by Chiwitel Eijifor as the most deserving performance, but at this point, we’re mincing the discussion finer than it needs to be.)

While he’s billed as the lead, is on screen for over 90% of the film, and commits a marvelous performance to celluloid, McConaughey is still far from the best performance in the film. That honor belongs to Jared Leto. As Rayon, a transgender man afflicted with AIDS, he absolutely disappears into the part. There are simply few words that suffice to convey how utterly brilliant Leto is. Rayon is a victim of her own vices, yet still maintains an air of sympathy that can and will bring tears to your eyes. Unrecognizable beneath a Marc Bolan-esque wig, Rayon steals every scene that she’s in, and drives a moral point home that almost transcends the script’s familiar and simplistic messages. We’re constantly asking whether Rayon has been pushed this far because of her own self-destructive impulses or because of how she has been treated and tormented throughout her life by family and friends, enabled by those she keeps close to her and at arm’s length (a lifelong friendship with Jennifer Garner’s vague doctor character is described at one point, briefly imbued with honesty by Leto, and then never discussed again). If at all possible, this performance is more brutal and painful to watch than Requiem for a Dream, while infinitely more entertaining…in its own way.

There are two particular scenes that stand out from the entirety of the film, both involving Leto. The first involves Rayon dressing as a man to make a dying request of her estranged father; the Buyers Club needs cash and Rayon needs her dad to sell her life insurance policy so that they can continue to serve those in need. Leto has the immensely challenging task of putting on a front while still playing Rayon (which, speaking as an actor, is really fucking hard to do), and pulls it off with heart-breaking intensity. We ache for Rayon, which makes her final spiral towards death all the more brutal. As her boyfriend dances on her bed, Rayon succumbs to a violent, bloody coughing fit as her lungs liquify. The look of terror and mortality on her face as she exclaims “I don’t want to die” was enough to drive a theater filled with patrons to tears, your faithful columnist included. Leto has been winning all the trophies this year, and deserves them all.

The merits and quantifiable value of acting in film is a debate with no right answer; ultimately, the best movies are the ones that fire on all cylinders (acting, direction, writing, cinematography, editing, etc.). It remains the opinion of this columnist, however, that acting is visual storytelling, and without actors, or specific actors playing iconic roles, many of our greatest movies would suffer. Imagine if anyone but Marlon Brando played Don Vito Corleone, or if Robert Duvall played Jake LeMotta, or if Ronald Reagan was the one staring at Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca. McConaughey and Leto take a film that might have been an utterly forgettable biopic about how AIDS is bad (don’t get me wrong, it’s terrible, and a part of our history that we should not overlook or forget) and allow it to briefly transcend its own limitations. If it deserves any kind of legacy, it should be as part of a cinematic textbook-reel that is shown to acting classes as an example of how actors as their best can simply disappear into their roles, telling stories that no one else can tell.