Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, but he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

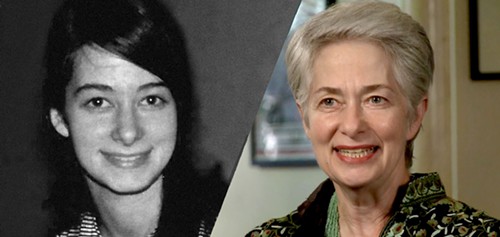

In 1969, the directories of Chicago counseling services began including a group known only as “Jane.” Jane did not provide psychiatric help or twelve-step programs. Jane—organized by UChicago student Heather Booth—was a network of sympathetic doctors and trained women who provided safe abortions, operating in various apartments, ready to flee at a second’s notice. Jane performed 11,000 abortions, and potentially saved and improved as many lives, by the time of Roe v. Wade.

This was a story I’d never heard before.

She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry: A Forgotten History Retold

That I know about it now is thanks to Mary Dore’s She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, a documentary that defines the term “must-see.” Over two decades in the making, and only finished thanks to a Kickstarter bounty, Dore uses extensive interviews and remarkable archival footage to tell the story of the feminist movement in the 1960s and early 1970s. It is a story easily glossed over or misunderstood; in today’s climate, where feminism is too often seen as a dirty word and too many women proudly declare themselves to not be feminists, it can get hard to remember that until the 1960s, women’s public lives, private lives, and bodies were more than circumscribed by a patriarchal system; this state was (and in many ways still is) accepted and unchallenged, with any deviations looked down upon.

She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry chronicles a moment of social challenge, when women inspired by Betty Friedan and others began simply meeting and talking about their lives. From these small beginnings, a force arose in America that marched in the hundreds of thousands and brought about a wave of social change, culminating not only in Roe v. Wade but also in Congress passing a law that would have guaranteed universal child care. This bill, which I had never been aware of, was vetoed by Richard Nixon—along with his sabotaging of the Vietnamese peace talks one of the two worst moments of his career—because he didn’t want children raised the way they were in the Soviet Union.

The child care bill and Jane are two of many pieces of history Dore works into an all-too-short but comprehensive ninety minutes. She explores many facets of feminism: the outspoken sub-movements of black and Hispanic feminists, the foundation of feminist presses such as Shameless Hussy, and the Lavender Menace that successfully demanded the movement acknowledge lesbians (whom they defined as “the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion”). And it has a strong Chicago connection, with profiles of Jane, the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective, and the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band, as well as a wonderful clip of WITCH—Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell—casting hexes in Hyde Park.

Tragedy and Triumph

This comprehensiveness includes the movement’s failures. That there had to be minority submovements speaks to the subtle discriminations within feminism, and the interviewees reveal that the reason women never had a King or Chavez figurehead was that, in an effort to not copy the patriarchy, any woman who got too powerful or public would be quietly pushed aside. And of course, the defeat of the child care bill (which has never been reintroduced) and the right wing’s current assault on women’s rights are addressed with sadness and anger.

Ultimately, though, She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry is a film of joy and recognition of triumph. Dore’s interview subjects, who include Rita Mae Brown, Kate Millett, the late Ellen Willis in one of her final appearances, and the Boston Women’s Health Collective (authors of Our Bodies, Ourselves) are forthright, hilarious, and inspiringly proud. “Don’t tell me ordinary people can’t change things,” one proclaims, “because I saw it happen.”

I was fortunate to see She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry at its opening weekend at the Music Box, with Dore present and answering audience questions. Encouraging people outraged by the backslide of women’s health to take action (“You don’t have to be angry, but sometimes it’s useful.”), Dore further urged that people follow the early feminist’s example and meet not on the internet but in person. “If it wasn’t for consciousness raising, women wouldn’t have admitted they were raped, they’d been battered, they’d had abortions. Consciousness raising is what leads to change.” Dore may be too humble to admit this, but her film is a bona fide consciousness raiser.

The Duke of Burgundy: Sex and the Single Lepidopterist

Interestingly enough, I happened to see another movie earlier that same day at the Music Box which was a complement to She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry.

English writer/director Peter Strickland shot to international attention three years ago with Berberian Sound Studio, a tribute to Italian giallo films. Strickland has followed this up with The Duke of Burgundy, a picture that similarly honors and probes the meaning of another cult genre, in this case the European erotic cinema of the 1970s.

Strickland employs many touches of the era, including the stylized opening credits (which identify the lingerie and perfume manufacturers), opulent sets, inconsistent production values (there are scenes with deliberate lens flare, and some of the crowd shots have obvious mannequins mixed in with the real people), and lush music, here provided by British chamber pop group Cat’s Eyes. But the filmmaker uses these tropes in the service of telling a story that is not mere pornography but takes on the qualities of a dream.

The Duke of Burgundy takes place in a world that seems to have electricity but no motors or advanced technology. There are scenes of palatial libraries and lecture halls (which are erotic for a bibliophile like myself) and people travel with bicycles. The entire population is obsessed with lepidoptery, studying butterflies and attending lectures on their biology (the title comes from a particular species). Finally, that population is entirely female.

The film focuses on two of these women: Cynthia (Danish film star Sidse Babett Knudsen), a middle-aged biologist, and Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna), her twentysomething student/domestic. Within the first twenty minutes, the BDSM relationship of the two is firmly established, but the rest of the movie sees the audience perception of their roles and desires within their union continually shocked and subverted.

Despite the strength of those verbs, there is little conflict in the film, and what conflict there is ties into the imagery surrounding its title. The butterfly is a metaphor for personal awakening, as it begins life as a caterpillar, goes into its own personal cocoon, and is transformed. Yet after that transformation, it can so easily be caught and pinned down. Similarly, Cynthia and Evelyn both have firm ideas of who they are as people, but their relationship often leaves one and/or the other feeling trapped for very different reasons. The film is about their attempt to not be trapped, and it is a mature document of how we keep our own identities in relationships while still harmonizing with our partners. Sex is presented as something beautiful, natural, private (The most imaginative things Cynthia and Evelyn think up, which require specially built devices, aren’t even depicted.), and above all, consensual–for the movie turns on how the two women work at their relationship to a point of mutual satisfaction, which is a refreshing theme.

Despite the sympathetic portrayals and Strickland’s commitment to directorial flair, The Duke of Burgundy ultimately has two problems. First, it’s boring for long stretches. Watching people engage in foreplay and sex over and over is like watching someone play video games; you’re meant to do it yourself, so vicarious experience doesn’t cut it and repetition only increases the apathy.

The second problem was one I couldn’t put my finger on until conversing with longtime friend of the Recorder Emily Steers: to wit, The Duke of Burgundy is ultimately a film written, directed, and photographed by men about 104 minutes of kinky lesbian sex. Kinky lesbian sex that didn’t necessarily have to be, for as Steers pointed out, if this was a film about a heterosexual relationship, then the themes wouldn’t change. Every lavish scene, including the one pictured above, is completely framed through a male gaze obsessed with the carnal possibilities of this manless world, and that ultimately leaves a bad taste in one’s mouth…which makes me very happy I saw it first, before the rousing message of She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry.

Photographs from the Chicago Reader, Bryn Mawr University, and Zetaboards. For Visit www.shesbeautifulwhenshesangry.com for more information about the documentary. The Duke of Burgundy is available on iTunes.