Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, and he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every week, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

The Peanuts Movie is a film I had the most mixed feelings imaginable about upon hearing of its production. One of the most unfailingly joyful parts of my childhood was discovering and devouring Charles M. Schulz’s world. This went beyond devouring the books and television specials. I would read out loud and give every character a distinctive voice, and some of the first stories I ever made up were further adventures for Charlie Brown, Snoopy, and the gang, and as I grew older and learned more about the deeper philosophical meaning of Peanuts (most recently well summarized by Todd VanDerWerff in Vox), I fell in love with the strip more. Peanuts is a part of me.

The last film adaptation was released four years before I was born, and when I heard the new movie was a joint effort of BlueSky, 20th Century-Fox, Paul Feig, and the Schulz family, I felt a sense of promise. But it was also a 3-D movie for the most 2-D of characters, and the history of Peanuts in cinema sets a poor precedent for this film.

The Predecessors

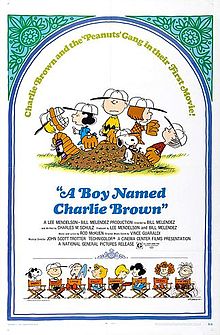

People who care about Peanuts and popular American art in general need to seek out the first film Schulz, Bill Melendez, and Lee Mendelson worked on after the classic original specials, 1969’s A Boy Named Charlie Brown. Pauline Kael, who was a Peanuts fan, criticized the film for not capturing the spirit of the comics, but she could not have been more wrong. This is an easy misjudgment to make, for Melendez and Mendelson used the expanded budget and canvas of film to do many things that couldn’t fit into a 23-minute TV cartoon. Boy is filled with surrealistic sequences mixing experimental animation, photography, and instrumental music in place of dialogue, including an evocative segment of Schroeder playing Beethoven’s “Pathetique Sonata,” Snoopy ice-skating in Rockefeller Center, and a nightmarish portion in which Linus stumbles like a drunk through a dark New York City searching for his blanket. But at the core of the movie is one of the definitive Charlie Brown tales; the round-headed kid struggles with self-doubt, ambition, and his great desire for friendship as he ends up competing in the National Spelling Bee, with Lucy Van Pelt serving as the outspoken, concrete representation of all his fears and neuroses. It is a film with a technically unhappy but inspiring ending, set to Vince Guraldi’s music and a fitting title song by Rod McKuen.

People who care about Peanuts and popular American art in general need to seek out the first film Schulz, Bill Melendez, and Lee Mendelson worked on after the classic original specials, 1969’s A Boy Named Charlie Brown. Pauline Kael, who was a Peanuts fan, criticized the film for not capturing the spirit of the comics, but she could not have been more wrong. This is an easy misjudgment to make, for Melendez and Mendelson used the expanded budget and canvas of film to do many things that couldn’t fit into a 23-minute TV cartoon. Boy is filled with surrealistic sequences mixing experimental animation, photography, and instrumental music in place of dialogue, including an evocative segment of Schroeder playing Beethoven’s “Pathetique Sonata,” Snoopy ice-skating in Rockefeller Center, and a nightmarish portion in which Linus stumbles like a drunk through a dark New York City searching for his blanket. But at the core of the movie is one of the definitive Charlie Brown tales; the round-headed kid struggles with self-doubt, ambition, and his great desire for friendship as he ends up competing in the National Spelling Bee, with Lucy Van Pelt serving as the outspoken, concrete representation of all his fears and neuroses. It is a film with a technically unhappy but inspiring ending, set to Vince Guraldi’s music and a fitting title song by Rod McKuen.

Three more Peanuts movies were made in the ensuing decade, and they learned the wrong lessons from A Boy Named Charlie Brown. These films, made as the Peanuts marketing buzz asserted itself fully, marginalized the human characters in favor of Snoopy and Woodstock. They were dominated by cheap dialogue-free animation of the beagle and bird trekking across America, riding motorcycles and rafts in battle against an evil cat, playing Wimbledon, and hitting up French taverns. These plots bore little relation to the comic strip. The music was the work of faceless journeymen or the inappropriate Sherman Brothers. This was product, pure and simple, and it was not my Peanuts or anyone else’s Peanuts.

Hence my delight when The Peanuts Movie proved itself to be a worthy addition to the legacy.

Why The Peanuts Movie Works

The Peanuts Movie is a movie which reflects the strip’s fifty-year span in every minute of its running time, on both macro and micro levels. The main plot is a Schulzian ur-story: Charlie Brown sets out to cast aside a lifetime of failure so he can make a great impression on the Little Red-Haired Girl. In this framework, a screenplay co-written by Schulz’s son and grandson fits in as much of the Peanuts mythos as it can: the sports, the kite-eating tree, Snoopy’s typewriter, the brick wall, the unrequited crushes (Sweet baboos and sly dogs, anyone?), security blankets and pianos and naturally curly hair, direct quotations from multiple strips, and so much more. This has the drawback of cluttering the movie, but thankfully the most faithful part of the adaptation is Schulz’s tone. Charlie Brown swings between insecure depression and an irrepressible willingness to keep trying. When he declares himself a “nobody” the sentiment is so plain-spoken as to ring true, but his endurance, and the empathy he has for others due to his own emotional struggles, slowly builds to a great finale. The film also capture Charlie Brown’s friendship with the intellectual and admiring Linus, constant lambasting from Lucy, sibling regard for free-spirited Sally, and exasperation and devotion alike between him and Snoopy. In most of the films and specials Snoopy was depicted as superior to and more interesting than Charlie Brown, but here the boy and his dog are connected as equals.

All of this is handled by director Steve Martino with an appropriate use of 3-D. Martino and his animators don’t attempt to make the film with the dimensions and texture of Pixar, which was never Schulz’s style. Instead the 3-D is used to bring a Peanuts strip to life, with the characters popping out of the backgrounds and moving with fluidity. The art is a terrific copy of Schulz, with the exception of one part of the film where the elaborateness and vibrancy get ratcheted up. In a parallel to the main story, Snoopy and Woodstock write a tale of the World War I Flying Ace piloting the Sopwith Camel on a mission against the Red Baron. These sequences are full of lavish detail, right down to the barbed wire trenches and Parisian streets, and the aerial combat has a child-friendly exhilaration. A part in which Snoopy’s fantasy escape across no-man’s-land intercuts with the reality of him running wild through the neighborhood is delightful.

All of this is handled by director Steve Martino with an appropriate use of 3-D. Martino and his animators don’t attempt to make the film with the dimensions and texture of Pixar, which was never Schulz’s style. Instead the 3-D is used to bring a Peanuts strip to life, with the characters popping out of the backgrounds and moving with fluidity. The art is a terrific copy of Schulz, with the exception of one part of the film where the elaborateness and vibrancy get ratcheted up. In a parallel to the main story, Snoopy and Woodstock write a tale of the World War I Flying Ace piloting the Sopwith Camel on a mission against the Red Baron. These sequences are full of lavish detail, right down to the barbed wire trenches and Parisian streets, and the aerial combat has a child-friendly exhilaration. A part in which Snoopy’s fantasy escape across no-man’s-land intercuts with the reality of him running wild through the neighborhood is delightful.

The Peanuts gang is played by children with scant acting experience, and what these talents lack in professionalism is made up for by the realistic tenor of their voices. Wisely, the film uses the archived voice of Bill Melendez for Snoopy and Woodstock’s inspired conversation, and Kristin Chenoweth copies Melendez’s mannerisms and cadence to play Snoopy’s love interest Fifi. Equally wisely, the only tie to 2015 is an inoffensive Meghan Trainor song. Christophe Beck mixes his playful score (which includes a charming love theme for Charlie Brown and the Little Red-Haired Girl) with Guraldi’s music for A Charlie Brown Christmas, still timeless after fifty years.

Having said all this, I come to what for me is an unusual conclusion. The Peanuts Movie is not a great film and definitely will not make my best of the year list. The need to clutter it with every possible reference lessens the screenplay, and BlueSky’s animation can be clumsy: there are some scenes where the framing appears off-centered or heavily spliced.

But The Peanuts Movie is also not aiming for greatness in the sense by which we usually judge great movies. This is not a movie of Pixar’s ambition, DreamWorks’s irreverence, or the anarchy of the Minions trilogy. This is Charles M. Schulz’s gentle and wise vision of humanity reverently retold, fifteen years after his death, to introduce the younger generations of this new century to Peanuts. This reverence makes it a limited movie, but it succeeds so well in its primary goal that I would call it a must-see: a film our readers should experience with their children, their nieces and nephews, their little cousins. The older generation will be awash with knowing reminiscence, and the younger may be introduced for the first time to what Peanuts is and may be inspired to turn to that most enduring of American comic strips.

The Peanuts Movie will help keep Peanuts alive and this is worth all the nickels that could ever be tossed into Lucy’s psychiatry booth.

Photos from Cartoon Brew, The Huffington Post, Wikipedia, and Tribute