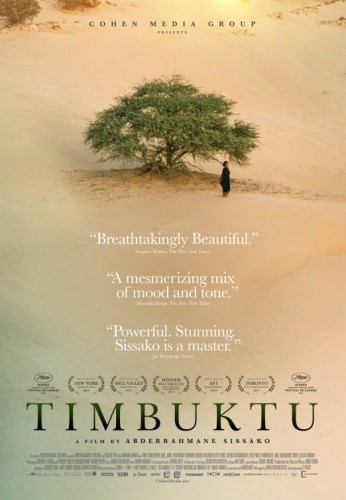

There’s a lot to talk about in Timbuktu, a film by Mali-born director Abderrahmane Sissako that received a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards, losing to Ida. It’s a gorgeous film, a harrowing film, and one that’s not as easy to wrap your head around as, say, American Sniper. Not that there’s anything wrong with that – Timbuktu just has a lot to say, and says it remarkably well.

There’s a lot to talk about in Timbuktu, a film by Mali-born director Abderrahmane Sissako that received a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards, losing to Ida. It’s a gorgeous film, a harrowing film, and one that’s not as easy to wrap your head around as, say, American Sniper. Not that there’s anything wrong with that – Timbuktu just has a lot to say, and says it remarkably well.

Communication Breakdowns

The basic premise of the plot concerns the takeover of the ancient trading center of Timbuktu, currently a dusty little town in the center of the African nation of Mali, by the jihadist Ansar Dine regime. The film consists of several montage-style scenes showing the jihadists interacting with those who call the region home. Throughout the film, we see the jihadists trying to communicate with the residents of Timbuktu. Always, there is some form of barrier – there’s always a translator hanging out acting as an intermediary between two groups who cannot communicate with each other.

The basic premise of the plot concerns the takeover of the ancient trading center of Timbuktu, currently a dusty little town in the center of the African nation of Mali, by the jihadist Ansar Dine regime. The film consists of several montage-style scenes showing the jihadists interacting with those who call the region home. Throughout the film, we see the jihadists trying to communicate with the residents of Timbuktu. Always, there is some form of barrier – there’s always a translator hanging out acting as an intermediary between two groups who cannot communicate with each other.

While it’s easy to mentally imagine Mali as an impoverished third-world country (not far from the truth), the film goes to length to show that western civilization has crept in through multiple channels. Furthermore, the film goes to show just how disjointed any and all efforts at communication have become. Characters all have cell phones – for which they are constantly trying to find reception. A newly recruited jihadist tries to record a video message – but is unable to make it feel as though it comes from the heart. The central story turns upon a cow named GPS – when the cow is killed, so too is any chance of figuring out where the characters stand in a world turned upside down.

A Corrupted World…

The film does an excellent job of humanizing the jihadists – in the times we live in, it would be all too easy to portray them as evil, nihilistic buffoons. However, the film shows that they are as human as anyone. Early on, a decree is issued banning smoking. Later on, we see one of the leaders of the jihadists hiding behind a dune smoking a cigarette. “Everyone knows you smoke,” says his companion, who has been teaching him to drive a stick-shift pickup truck.

The film does an excellent job of humanizing the jihadists – in the times we live in, it would be all too easy to portray them as evil, nihilistic buffoons. However, the film shows that they are as human as anyone. Early on, a decree is issued banning smoking. Later on, we see one of the leaders of the jihadists hiding behind a dune smoking a cigarette. “Everyone knows you smoke,” says his companion, who has been teaching him to drive a stick-shift pickup truck.

As the story progresses, we see the invaders imposing a series of strict edicts upon the populace. What’s most intriguing is that this populace is not composed of Christians or non-Muslims – the city and country are devoutly Muslim. During one scene, a group of jihadists hunt down some singers late at night in the city, enforcing a decree that has banned music. When the fighters arrive at the source of the music, they find the musicians to be singing in praise of Allah and the Prophet. “Should we arrest them?” asks the guard.

There’s a sense of corruption that bleeds through the actions of everyone and everything, as though the very presence of the jihadists has poisoned the community around them. The owner of the aforementioned cow, a nomad named Kidane, at one point angrily confronts the killer of his beloved “GPS”. He goes armed, intending to show strength – as with any story, tragedy unfolds, and the gentle, music-loving Kidane becomes a killer. He confesses to his crime and says that he will accept whatever punishment is deemed appropriate by Allah – the jihdaist judge rushes through the trial, pushing straight to a punishment even though the aggrieved mother of the victim says “I cannot forgive today….maybe tomorrow.” A quote from Sissako says that he feels that allowing time for decisions is an important facet of the law – with that in mind, more of the scene’s corruption makes sense.

…and Still a Beautiful World

Timbuktu is a beautiful film. The scene of the killing is breathtaking in both its depth and framing. A shot of an eccentric woman considered a “witch” by the jihadists walking spread-armed before a convoy lingers in the memory, rife with potent religious imagery. The golden sand dunes of the nearby desert are interspersed with stark green trees. This is a beautiful land that cannot be contained by the no-frills jihadists…who are not without frills themselves. During a stoning of an unnamed couple, a jihadist dances in the sand – the juxtaposition of brutal murder with airy, impassioned dance makes for one of the most intense scenes I’ve witness in film in recent years.

Timbuktu is a beautiful film. The scene of the killing is breathtaking in both its depth and framing. A shot of an eccentric woman considered a “witch” by the jihadists walking spread-armed before a convoy lingers in the memory, rife with potent religious imagery. The golden sand dunes of the nearby desert are interspersed with stark green trees. This is a beautiful land that cannot be contained by the no-frills jihadists…who are not without frills themselves. During a stoning of an unnamed couple, a jihadist dances in the sand – the juxtaposition of brutal murder with airy, impassioned dance makes for one of the most intense scenes I’ve witness in film in recent years.

Later on, viewers witness a soccer game where the players kick around an imaginary ball – since soccer has been banned by the jihadists, the locals make do as best as they are able. Musical undercurrents run throughout the film, in spite of its banishment by the foreign jihadists. Kidane sits up at night playing guitar for his family. Later, we see a roomful of young adults sitting and playing music together. When they are caught and the singer is sentenced to 80 lashes, she sings in defiance during her punishment.

It’s a message of hope in the face of bleakness. The final shot of the film shows a young girl either running towards or away from the demise of her parents. Depending upon how you interpret the film, you can either believe that the situation in Timbuktu will improve or will degrade even further. Personally, I believe that Sissako is saying that such repression cannot last forever and that the spirit of individuality forever strives to be free. In a world where ISIS dominates the headlines, it’s a much needed message.