Friday, September 18 at 6:30, Chicago hosts one of its best annual free events. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra will perform their “Concert for Chicago” at Millennium Park with two classical masterworks from the nineteenth century. It will be a great night for wine-and-cheese picnics and quality time under the stars (or the Pritzker roof if it rains), but some people may feel unsure about attending a show where they know little to nothing about the performance. Hence, the Addison Recorder offers this handy primer!

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Founded in 1890 and receiving their current name in 1913 after being known as the Chicago Orchestra (no Symphony required) and the Theodore Thomas Orchestra (after their first conductor, who inspired a Pulitzer-winning biography and when initially offered the job said “I would go to hell if they gave me a permanent orchestra.”), the CSO has garnered sixty-two Grammies and more international platitudes than we could list in ten articles. Their most famous music director was Sir Georg Solti (1969-1991), whose giant head is forever enshrined in statue form in Grant Park. And if you have to ask how bona fide Chicagoan they are, they perform in a concert hall designed by Daniel Burnham.

Riccardo Muti

The 74 year-old Muti was born in Naples and has never cut ties to his native country. Muti spent nineteen years conducting at La Scala, only to leave after clashes with the administration led to the employees delivering a no-confidence vote. Even as a guest conductor Muti can stir up controversy: in 2011 at Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera, he broke classical music protocol (and as a former musician, let me say there is a lot of protocol) by stopping a Verdi opera and delivering a speech to the audience on the slashes to national arts funding instituted by Silvio Berlusconi. To this day, even though he took the post of CSO Music Director in 2010, Muti conducts the Orchestra Giovanile Luigi Cherbini, which he founded to only employ Italian musicians under 30. However, Muti has definitely warmed to the Second City, as his passionate conducting and videos like this show:

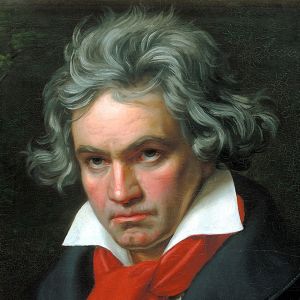

Leonore Overture No. 3 (1806) by Ludwig van Beethoven

There isn’t much we need to say about Ludwig van Beethoven, one of only a few composers with a personality as famous as his music, which is good because the story behind Leonore Overture No. 3 is convoluted enough. For one, it’s from Beethoven’s only opera, titled, of course, Fidelio. The opera tells the story of Leonore (bear with me) who disguises herself as a prison guard named Fidelio to rescue her nobleman husband Florestan, a man imprisoned for trying to expose government corruption and about to be murdered. Beethoven wrote Fidelio in the wake of the “Eroica,” his great third symphony whose dedication to Napoleon was blotted out when the First Consul declared himself Emperor. Fidelio is linked with “Eroica” as a work celebrating Beethoven’s political ideals (freedom and justice conquering tyranny) but it is also an opera, so to please the masses there is a second plotline in which the head jailer’s daughter falls in love with Fidelio, to the dismay of the jailer’s assistant who loves the daughter, and they get a four-part canon to sing about it.

Beethoven spent almost a decade tinkering with Fidelio, reducing it from three acts to two and composing four different overtures. Leonore Overture No. 3, which was chronologically the second (yes, I’m getting a headache as well) is also considered the best. Beethoven’s overtures were designed as aural stories with dramatic structure, rises and falls, and a breathtaking finish, all suitable for an opera which boasts numbers such as “Now old man, we must hurry!” “Scum! Where are you going?” and “How cold it is in this underground chamber…get to work and dig!”

Symphony No. 1 in D Major (1888) by Gustav Mahler

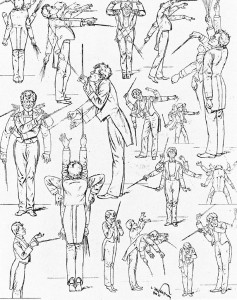

A fantastic caricature of Mahler conducting from the German satirical magazine “Fliegende Blatter,” 1901

Gustav Mahler is one of the patron saints of those who get paid for their day job while pursuing their passions in their off-hours. Fortunately, Mahler’s day job was as a conductor—one of the greatest of his era, no matter how much he would have preferred to be composing.

Born in 1860 in Bohemia, the grandson of a peddler and son of an innkeeper, Mahler worked his way through the ranks of various orchestras until in 1897 he became conductor of what is now the Vienna State Opera. Mahler made his international reputation in Vienna, especially for his productions of Wagner and Mozart, but when he was asked to become conductor of the Metropolitan Opera in 1907, he said yes immediately. Mahler led both the Met and the New York Philharmonic before he died of heart failure in 1911.

Mahler’s years of professional success were marred by personal aggravation. The Jewish Mahler converted to Roman Catholicism upon his appointment in Vienna to please Austria’s anti-Semitic power elite. He frequently quarreled with the opera staff, especially when he spent more time on his own music. And his marriage to fellow composer Alma Schindler was so fraught with passion and tumult that to this day musicologists frequently refer to “the Alma problem:” Alma outlived her husband for so many decades that her writings drastically influenced the public understanding of Mahler. That he produced an extraordinary collected opus under these circumstances is a testament to his genius.

Mahler worked only in two forms: song cycles and symphonies, of which he wrote nine and was working on the tenth at his death. The symphonies were sometimes indistinguishable from the song cycles. Mahler abandoned the classic four-movement structure and based his symphonies, some of which featured choral parts, around multiple strong, song-like melodies arranged for frequent tonal and harmonic shifts. The result was an unusual but memorable style that I like to describe as full of surprise and delight: one can never fully predict the next turns Mahler will take but those turns are always logical. Many of his compositions was unappreciated in its own time but gained posthumous reverence as several conductors, Leonard Bernstein most vocally, championed Mahler.

Mahler’s First, written in 1887-88, has a history almost as complex as Beethoven’s overture. It is still referred to in some recordings as “Titan,” a name Mahler himself gave it in its first performance, but which he subsequently retracted, along with his original program notes and a fifth movement which was placed between the first and second. The composer even referred to it as a tone poem in the beginning and only later acknowledged it as a full symphony.

Whatever and however it is labeled, the First Symphony, scored for over 100 instruments, is a work with almost twice as many hummable melodies as the average piece of its sort, with a strong beginning and ending and a third movement that boasts a dirge arrangement of “Frere Jacques” that must be heard to be believed – and on Friday, you can hear it.

Images from Fine Art America, Wikimedia, Biography.com, and GustavMahler.com