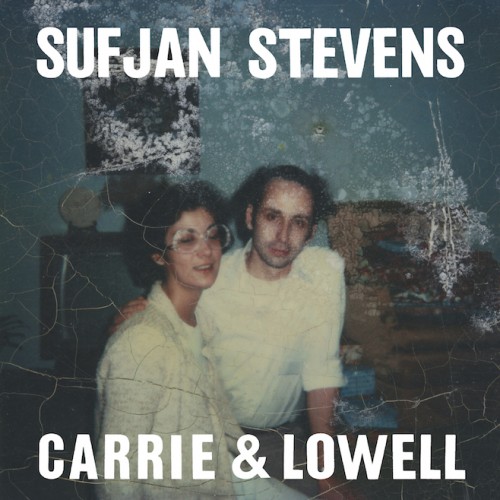

I’ve long been a Sufjan Stevens fan. He is an intelligent, clever songwriter who seems to enter every record with an ambitious plan and the determination to carry it through, and his finest songs are charged with the strongest emotional resonance, especially “Chicago,” which with its anthemic strings, inviting mass choir, and straining but hopeful lyrics, is a soundtrack for new beginnings. This is why it is all the more remarkable for me that Stevens, has made the finest album of his career and one of the best of 2015 with Carrie and Lowell, a record about the ultimate ending.

Old and New Styles and Lessons Learned

My major problem with Stevens thus far has been an inability to rein in his cleverness or ambitions. It often seemed that Stevens was so dedicated to his concepts that he needed to explore them to their fullest limits with no regard for the listener. He has not yet released an album under 65 minutes (meaning all of his albums would have been double vinyl back in the day) and I’ve never attempted to crack The Age of Adz with its 25-minute finale or the TWO five-disc Christmas records in their entirety.

This wouldn’t be a problem if his records were chock full of good ideas…and this may be something no one wants to admit, but here goes. For all the high points of the Fifty States project, Michigan and Illinois are slogs to get through, what with the unnecessarily long-titled snippets of noise and endless stretches of string/horn/keyboard repetition that sound, as one of my friends once put it, like music you’d have on when questing across Hyrule, not getting introspective.

Stevens’s new album, Carrie and Lowell, clocks in at under forty-five minutes, not one of them feeling wasted or extraneous. One has to imagine that Stevens had a filter on and a determination to only release the highest points of his new material, for like his earlier records, Carrie and Lowell is a concept album but one dealing with an even larger concept than the states. The two titular figures are Stevens’s mother Carrie, a schizophrenic alcoholic, and her husband of five years and Stevens’s stepfather, Lowell Brams, a man he respected so much that Lowell now helps run his record label. Carrie died of cancer in 2012, and after a long grieving period, Stevens wrote these songs in a brand new style.

A Gentle Sound

Carrie and Lowell has nothing in common with the grandiosity of “Chicago” and other larger-scale Stevens cuts, but does fall into the tradition of my personal favorite compositions of his, the melodic, low-key, quavering songs such as “Romulus” and “Casimir Pulaski Day.” The album is dominated by acoustic guitars, recorded so well that every individual pluck reaches the ears. Little accompaniment are needed, but one that makes a difference is the electric piano. Herbie Hancock once said that when Miles Davis first introduced him to the electric piano, it sounded as clear as a bell, and on songs such as “Fourth of July,” the piano rings like a carillon from the top of a cathedral.

The greatest instrument on the record is the human voice. Stevens’s vocals have always been sterling, but now, layering his parts, he sounds like Simon and Garfunkel entwined in one body, light but confident tenor mixing with airy, enticing falsetto. This is a valid comparison, for the overall gentleness of the album recalls the best S&G records. Yet…and this also may be something no one wants to hear…the songs on Carrie and Lowell possess a power rarely felt in Simon and Garfunkel or in most pop music.

An Epic Journey Without End

Stevens abandons pretensions, gimmicks, and easily digestible ideas as he confronts the pain of unconditionally loving someone when such love does not come easy and the even greater wreckage of losing someone to whom you give that love.

The first emotion is best expressed in a series of songs, including the title track, in which Stevens recalls childhood visits to Carrie and Lowell in Oregon. (Old habits die hard, as the record is peppered from beginning to end by references to cities and landmarks in the Beaver State.) The best of these is “Eugene,” a series of snapshots of childhood memories that sees Stevens declare “I want to be near you…what’s the point of singing songs if they’ll never even hear you?” These tracks are plaintive with the barest of melodies, and work very well.

The songs about death, however…many brilliant songwriters have meditated on the end of existence, and Sufjan Stevens’s songs rank with the best of these. The sensations of heartbreak, rage, and struggling towards acceptance are there, but what Stevens calls upon most sharply is the confusion: the struggle to realize that a constant of your life has been permanently taken away, and the ruminations on how that person might have thought and felt about you, how you are supposed to react, how to take the first step in moving on. Add in the undertones of Stevens’s Christian faith, and the result is an unadorned swirl of poetry, which he accompanies with some of the strongest and most unforgettable melodies of his career. You’ll feel a little strange humming them, but they will get stuck in your head.

The best of these, and maybe Stevens’s masterpiece, is “Should Have Known Better,” a five-minute journey through grief, from trying to hide it in an attempt to be strong for others to confronting that it has always been a part of your life (Stevens references frequent abandonment from his mother) and it must be let out. When Steven reveals who he is trying to be strong for—his “illuminated” niece—the song grows more poignant with the suggestion that life will carry on through all we lose.

The other strong point is the closing stretch of songs. “John My Beloved” finds Stevens searching for romance with a new intensity following this reminder of our mortality, admitting that “in a manner of speaking, I’m dead.” This unusual perspective works, and Stevens’s desperation carries over into “No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross.” Set to a tune reminiscent of the great American folk ballads, Stevens honestly confronts the great mystery of how faith and suffering intertwine, admitting to God that he is “falling apart.” But this journey finally “ends” in “Blue Bucket of Gold,” a prayer (his final lyric is “Lord, touch me with lightning”) that in a world where all passes away, he will find something permanent and lasting. That the record ends with a minute of electric noise is appropriately ambiguous. That Stevens is committed to his search, as expressed in the lyrics, is hopeful. We can never know what lies beyond our last day or what the future holds…but Sufjan Stevens has made a work of art that in its honesty offers empathy, and from there a spring of hope.

Photograph from Album of the Year