I am an unabashed lover of fairytales. My fondest childhood memories are mostly about my siblings and me sacking out on our parents’ bed while Mom read to us from an illustrated version of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytales. It opened with the “Emperor’s New Clothes,” which was fine. My little sister preferred “The Little Mermaid” or “The Little Match Girl,” but my favorite was the “Snow Queen.”

Gerda & the Reindeer (Edmund Dulac, illustrator)

I have no hate for Disney. I’d consider myself an affectionate if critical observer. I don’t really go in for dressing as a princess, but the Disney Marathon is on my bucket list. I know and understand the problems with ‘Princess’ culture—the idea that women need to be rescued from isolation or the control of our parents, that we need marriage (and therefore sex) to become adults and understand the world—yep, that’s all troubling. There’s been a lot of criticism written about it — just Google “problems with Disney princesses” and you’ll get results from The Week, the Boston Globe, and a host of bloggers. That said, I will still sing along with every single Disney song written between 1989 and 2000.

Thus, I was tentatively delighted when I heard that Disney’s newest conquest was to be my favorite fairytale. Like most girls born in the mid-’80s and early ’90s, I grew up in a world surrounded by Disney princesses. Belle was my favorite — a brown-haired bookworm with a taste for adventure (total projection fodder). I could take or leave the prince at that age, but then as now, I fantasize about spending hours in solitude in the castle library. Add to general Disney magic the talents of Idina Menzel (Wicked, Rent, Glee, awesomeness) and Kristen Bell of Veronica Mars fame, and Frozen had definite potential.

I knew Frozen wouldn’t have much to do with the original fairytale as soon as I started seeing promotional materials. After all, the original story was about neighbors, a boy and a girl, and the boy runs away with the Snow Queen, the villain of that story. That’s definitely not the plot of Frozen. Gerda and Kai are nowhere in sight.

The key word here is “inspired.” This movie is inspired by “The Snow Queen,” not based on it. If I had to guess how they got from the classic fairytale to the movie, I’d guess that they started with the question: “How did the Snow Queen become the Snow Queen? What if her life had happened differently?”

“The Snow Queen” is another step away from the common tropes of the Disney Renaissance. It is a story about innocent love. Gerda’s innocence and perseverance are the qualities that allow her to find and save Kai, her tears destroying the shard in his heart and allowing him to clear the mirror shard from his eye. Disney, in the past, has favored romantic love as a transformative force (Beauty and the Beast and the Little Mermaid show this in a very literal sense). Brave was a refreshing step away from this when it spotlighted the mother-daughter relationship. Frozen is another step in the right direction.

How do you keep the Snow Queen from becoming the Snow Queen? Give her a sister, apparently. Frozen is a story about siblings, about women coming into their own, facing challenges, and saving themselves. “The Snow Queen” was a story about women in many ways—female protagonists, women that aid Gerda all along the way, yet in many ways, Disney’s Frozen has a lot more to offer the modern woman because the characters are allowed to grow up, while the Snow Queen is about the characters maintaining the hearts of children. In Frozen, the two main characters, Elsa and Anna, begin the story as close friends, sisters who delight in each other until one day Elsa accidently injures her sister with her powers. For some hand-wavium-type reason, Anna has knowledge of her sister’s power wiped from her mind, and Elsa must hide her cryokinetic skills. Because it’s a fairytale, the parents die tragically before the girls come of age, leaving the girls alone and Elsa still isolated. A few years later, Elsa is finally old enough to be crowned queen and things get real when Anna gets engaged to a total stranger named Prince Hans during celebration. Because getting engaged to someone you’ve known for less than a day is completely absurd (!!), Elsa refuses to give her blessing, loses her temper, and puts the city into a deep freeze.

Let’s pause a minute here and drink that in: Disney called attention to the absurdity of their own trope. Yes, the whole “We shall be married tomorrow!” thing was poked fun at in Enchanted, but no one really counts Enchanted when they’re talking about Disney princess movies. Most of the comedy in Enchanted was watching fairytale expectations butt up against life in the real world. Brave skipped it because the main character wasn’t emotionally mature enough to handle boys and was too busy being awesome to think about marriage. Frozen gives us a young, idealistic protagonist who craves attention, new experiences, and romantic love, finds it, and then has not one but two—two!—other characters question her judgment.

Elsa flees into the mountains in a dramatic music moment. I adore this scene because it’s: (a) Idina Menzel, (b) visually awesome, and (c) a moment of character growth that has nothing to do with men or love. Elsa is pushed out of her isolated life and rebelling against being a good girl, and it has nothing to do with anyone else. Her sister and her anger are the impetus, but this growth is about giving up the vestiges of parental constraint. She’s declaring her freedom, finding out who she is as an individual when the expectations of others are removed and the rules don’t apply anymore. It’s gorgeous and triumphant, and has tangible and terrible consequences. Her exertion of her will on the world is fundamentally selfish. She can’t control herself—this is an adolescent thinking that she’s got it, she’s got control, knows who and what she is, and she glories in it. She’s sexy. She’s powerful. She’s comfortable in her isolation. This is the birth of the Snow Queen, cold, distant, and powerful.

Then Anna, the person for whom Elsa first shut herself away lest she harm her sister again, shows Elsa that this overabundance of freedom is destroying their home. In her rage and fear, Elsa lashes out and nearly kills Anna. Again. The first time Anna was hurt, Elsa accidently struck her in the head with magic and the trolls saved her life. This time, it’s her heart that’s in danger and only “an act of true love” can keep her from literally freezing solid.

Luckily, she just got engaged and has a true love’s kiss waiting for her at home, right? Prepare to be blind-sided by a red herring in another excitingly unexpected Disney plot twist. Oh, and at some point in there, Romantic Option 2 very sweetly asks Anna for permission to kiss her, which is Disney saying something very interesting and important about consent. Wow.

This is probably the most emotionally mature movie we’ve seen yet from Disney. It has messages that are appropriate to at least three different age groups, and while it’s a princess movie, the messages aren’t nearly as gendered as they seem on the surface. This is about how to be a sibling, how to care for siblings, and teaches the consequences of rash and selfish behavior in a way far less heavy-handed than the opening sequence of Beauty and the Beast.

Frozen isn’t perfect, of course. It’s missing the most important piece of sibling relationships, sacrificed for ease of storytelling and because Disney caved to one of the oldest fairytale tropes: death of the parents. In real life, siblings vie for love and attention from parents, and any perceived difference in how parents treat one sibling over another creates resentment, or at least discontent. Siblings ally with each other and fight with each other and it’s all to jockey for attention. Because of Elsa’s isolation, we don’t see her relationship change with Anna, but we also don’t see Anna change at all despite being seemingly neglected by parents whose attention is now focused on the problematic sibling.

(Credit where it’s due: when parents are gone, often the effect they have on their children becomes even starker as children try to live up to or throw off the chains of parents’ expectations. “Let it Go” is an incredible microcosm of that emotional journey. )

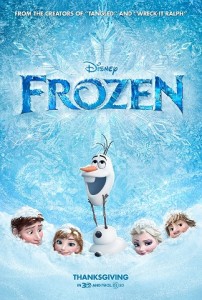

The character growth is uneven, but it fits the story and characters. Elsa seems to get first billing in the movie art, but Anna gets the guy and only a modicum of additional maturity. Meanwhile, Elsa experiences incredible character growth and there’s no romantic lead in sight. The pace drags a bit in the middle, but not too badly. Frozen also has its usual cast of fun side characters, including an animated talking snowman that doesn’t do much to move the plot forward, and a sassy reindeer in the Magic Carpet style of expressive silence. It’s a fun movie, and I’ll definitely be purchasing choice pieces of the sound track. I’m digging this new direction, Disney. Well done.

[…] Since Karen wrote her terrific review for us, Frozen passed Toy Story 3 to become the highest-grossing animated film ever made…it seems children didn’t mind that they got an emotional tale of two sisters learning self-discovery and acceptance instead of the romp with the talking snowman and the smart reindeer that the ads promised. One thing I noticed about Frozen when reading other reviews and placing them beside Karen’s (and this links back to an observation I made regarding Wreck-It Ralph that Disney was making movies taking into account our particular generation’s transition into adulthood) was that a general theme seemed to be running throughout most of the film’s criticism. Essentially, the running thesis seemed to be the following: Frozen was good; it could have been better. It was not as groundbreaking as we’d hoped it might have been once we caught on to the real story. However, we were ready to give it the thumbs up for what it did, what it aimed for, and what it promised for the future. It certainly was not the first Disney film to feature strong and determined female characters front and center, (ignoring Mulan and The Princess and the Frog would be a crime) but in making the central relationship between two women, by spitting in the face of Disney princess cliches regarding matrimony, dreaming instead of doing, and such, Frozen at the least showcased an awareness that is always the first step toward solution. […]