-J. Michael Bestul is a writer for the Addison Recorder. Stephanie Ruehl is an artist who works in a comic book shop. They’re married and have a lot of discussions about comic books and graphic novels. Combine all that into a biweekly feature and you get “J. & Steph Talk About Comics.”

As any industry or medium grows, it develops jargon — language that fans, practitioners, and others “in the know” understand, but can be an obstacle for new fans and practitioners. As someone who works in a comic shop, and who is an advocate for bringing in new fans, Steph wants to ensure that such technical terminology isn’t a barrier.

Here, then, are a few pieces of jargon that can help potential new fans and readers.

GUTTERS

Steph: “The gutters” has become a more well-known term–

-J.: Yup. It’s a now-defunct webcomic that used to skewer and editorialize the goings-on of the comics industry.

Steph: …or we could talk about the original meaning of the term. The white, or sometimes black, spaces between each panel are referred to as the “gutters.” They’re good places to insert your own idea of goings-on in-between the panels.

-J.: Ah, yes. “Gutters” refers to a unique aspect of sequential art layout — it’s the liminal space between the panels, the space where the narrative that we don’t see happens. In the film medium, stories are told by editing together visual elements in a sequence of moving pictures. Comics work in a similar manner, utilizing a page’s (and book’s) layout to edit together a sequence of static pictures to tell a story. Films have their “cuts” and comics have their “gutters.”

Steph: Books have chapters and section breaks, etc.

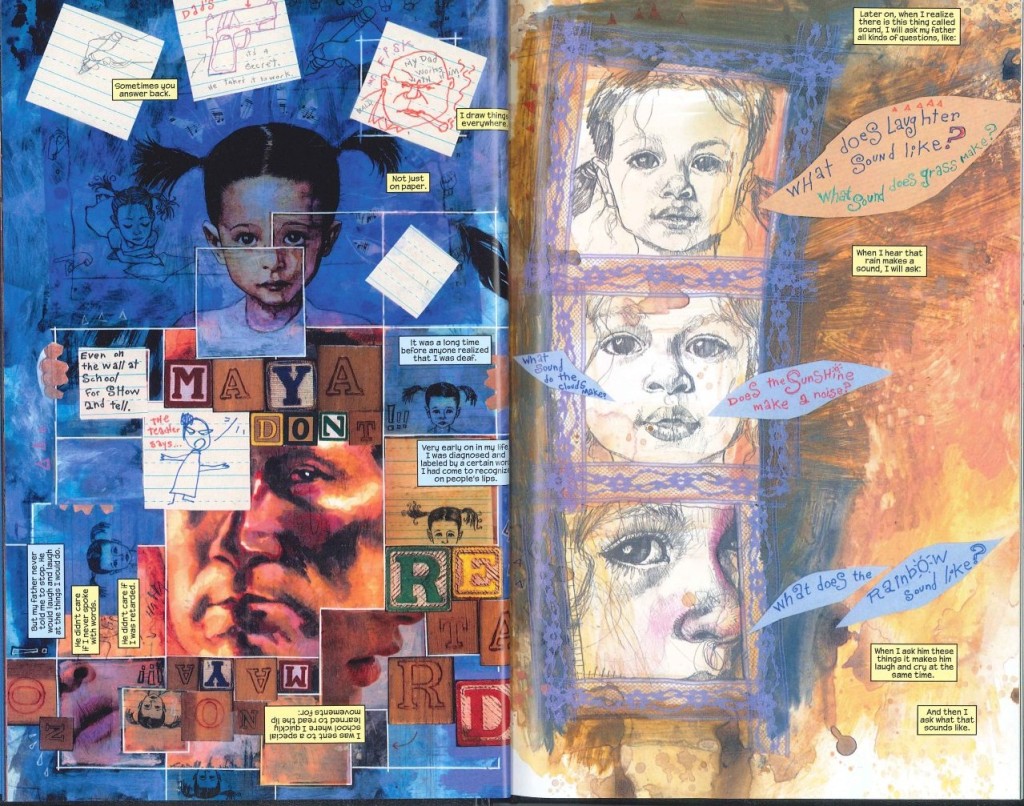

-J.: One of my favorite series to study image arrangement and how layout drives narrative is the Daredevil run under Brian Michael Bendis and David Mack, with art from Mack, Joe Quesada, and Alex Maleev. The art often challenges the expectations for clean lines, blank gutters, and standard reading.

TRADES

Steph: “Trades” vs. “graphic novels.” I’ve been a bit surprised at how many people I’ve discussed comics with who hadn’t heard the term “trade”. But I mean, why would they really? It’s jargon.

-J.: True, especially considering we comics fans use the term “trade paperback” in a different way from its original meaning. “Trade” was just a way for publishers to distinguish different sizes of paperbacks, from the “mass-market” size that most of us peruse in the book store, to the “trade” size that is bigger. Because comics are a bigger size than mass-market paperbacks, the collected volumes of comics series were published in trade paperback format.

Steph: As it’s now used in comics terminology, a “trade” is the collection of multiple, usually sequential, individual comic book issues. Typically there are about five issues within a trade. If you pick up a “volume one” of something (like, say, Rat Queens), it would contain issues 1-5 of the series, “volume two” would be 6-10, and so on.

-J.: That brings up one of the criticisms of modern comic books: the forced 5- or 6-issue arc. Since comics are (generally) a serialized medium, stories could take place over any number of issues. They could be self-contained in a single issue, or span across four, five, eight, or twelve issues. Trades used to be necessary because you might not always be able to find all the issues in a story arc.

Steph: Or it’ll happen that a lot of people who read comics, myself included, will wait for a trade to come out before buying and reading said comics. Since most ongoing books have story arcs that take place over the course of five issues, a trade will usually encompass a whole story arc. (And if you’re like me and read your comic books in trades, you understand the agony of waiting for each volume.)

-J.: That’s where the criticism comes in. It seems like EVERY contemporary story arc in mainstream comics is now exactly five or six issues. Comics are still being published in serial format, but the stories all seem to be written for when they’re packaged as a trade.

Steph: Like a season of a TV show. 12 to 24 episodes leads to an over-arcing story, ended (infuriatingly) with a cliff hanger. You can watch every week, or binge in one go. Either way it sucks waiting for the next season.

-J.: A couple of my favorite examples of how trades collected arcs of varying lengths (not just five or six issues) can be found in the James Robinson run on Starman, or Neil Gaiman’s groundbreaking Sandman series.

GRAPHIC NOVELS

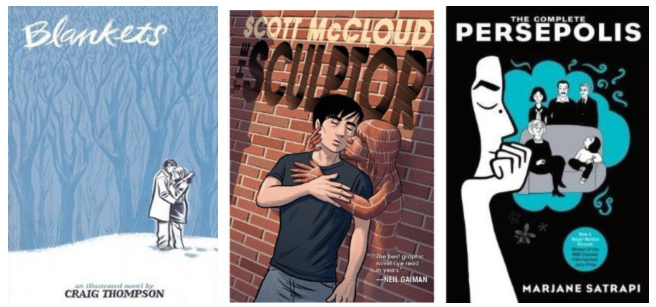

Steph: Theoretically, a “graphic novel” is a single story contained in one book. Blankets by Craig Thompson, the Sculptor by Scott McCloud, and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, are examples of graphic novels. The entire story is released in one volume instead of serialized into individual comic issues and released separately over time.

Steph: Theoretically, a “graphic novel” is a single story contained in one book. Blankets by Craig Thompson, the Sculptor by Scott McCloud, and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, are examples of graphic novels. The entire story is released in one volume instead of serialized into individual comic issues and released separately over time.

-J.: Part of the difficulty with comic book jargon is that it’s often interchangeable. Going back to my last examples, a lot of people will refer to the Sandman trades as “graphic novels,” because they are single stories contained in one book. They truly feel like self-contained books. But they were also published in serial format, so they would technically be trades. Hell, Watchman is considered the seminal graphic novel of the modern era, but it’s also a trade paperback collecting the 12 issues of a serialized comic book.

Steph: The terms “graphic novel” and “trade” are really interchangeable at this point. If you were to walk into a comic shop and ask after either, you’d most likely be directed to a book shelf containing both.

-J.: It’s also rare to find comic books that have never been serialized. Smaller publishers will release self-contained stories like The Reason for Dragons or The God Machine, or self-contained anthologies like the “Dark Horse Books of…” But even self-contained stories will often be released in serial format before printed as a trade / graphic novels.

REBOOT / RELAUNCH / RE-NUMBERING

-J.: This is where mainstream (and some smaller) publishers both welcome in and drive away potential new fans. As we’ve established, this is a medium that is often told in serialized form. But what if you want to start reading a series that is already in progress?

Steph: If you are interested in picking up a long running series, like Daredevil or Batman and have no idea where to start, a good place is to find a volume one.

-J.: Exactly. Find a trade marked volume one, or an issue marked #1, and go to town. This creates a recurring problem for mainstream publishers. When a series is popular enough to become long-running, almost all your issues are NOT #1. What to do?

Steph: The Big Two have rebooted and relaunched their universes a few times over the years, so they have multiple volume ones.

-J.: Right again: re-launch your titles with slightly different names. Reboot the series. Start re-numbering often and with gusto. The only problem is that this starts creating “#1 issues” that don’t read like a #1 issue, which can result in confusion and frustration.

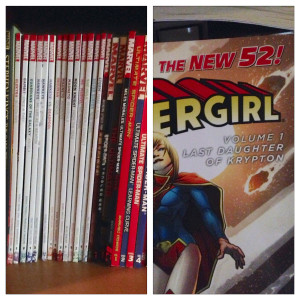

Steph: Lately I most often recommend starting with Marvel NOW! or DC’s New 52. If you check on the very first page they list what issues are collected in that trade and when they were first printed. The newest Marvel titles are easy to spot as they all have the same white spines, and the New 52 have ‘the New 52!’ printed in red on each cover.

Steph: Lately I most often recommend starting with Marvel NOW! or DC’s New 52. If you check on the very first page they list what issues are collected in that trade and when they were first printed. The newest Marvel titles are easy to spot as they all have the same white spines, and the New 52 have ‘the New 52!’ printed in red on each cover.

-J.: Starting this next month, however, all of that changes thanks to big crossover events!

CROSSOVER

-J.: Oh, crossover events. You so often excite and disappoint in equal measure.

Steph: Huge crossover events can be exhausting to keep up with.

-J.: A crossover event is when a publisher ties together separate series into a single, inter-connected storyline. This often necessitates you picking up either a bunch of issues from different series, or a central mini-series that contains the spine of the narrative. In many cases, unfortunately, it’s both.

Steph: Yup.

-J.: The first contemporary “crossover event” is credited to Marvel’s original Secret Wars. It was literally nothing more than a way to get a bunch of Marvel characters into a single series so they could sell more toys. Thirty years later, we still greet crossover events as potentially cool and epic stories — but worry that we’re just getting an over-hyped way to spend more money, or a rushed attempt to reboot branding and continuity.

Steph: With the recent Convergence and Secret Wars, I’m crossovered out.

-J.: Agreed. Personally, I loved what DC did with the year-long 52 event that followed Infinite Crisis. It played with the conventions of continuity, crossovers, and multiverses in a way that was compelling. It’s also one of the last big events I’ve enjoyed from DC…

To Sum It All Up: the Malleable Storytelling Medium

Steph: I think the best thing about comics is that they can be anything. A lot of people think comic books are all about superheroes, and where there are so very many superhero comics out there, that certainly isn’t all.

-J.: We get jargon from an industry as it grows and matures, but we are also finding wider options for our reading pleasure. It’s easier to go beyond the superhero titles of the Big Two publishers. (“Big Two” is another bit of jargon that refers to DC and Marvel, the two biggest publishers.)

Steph: There’s horror, and sci-fi, and fantasy, and westerns, and crime dramas, and non-fiction, and fiction, and every genre you can think of. Comics are a versatile medium that a writer or artist can plug virtually anything into.

-J.: And if you want your capes (superheroes), the Big Two are both rebooting all of their series, so now’s a good time to hop on.

Steph: Is DC actually rebooting?

-J.: Good question. That’s not the jargon they’d use, but they are using Convergence to re-prioritize, re-brand, and diversify after the flop that was the “New 52.” It just goes to show — even when you know the lingo, sometimes the industry will roll out another piece or jargon to describe it.