Some of you who have read my work here may wonder why I chose the graphic novel as my preferred form of literary expression as opposed to the classic prose novel, more Recorder-type essays, dramas of stage and screen, or sundry others. I will admit that comics present some surface challenges, especially for those who write but do not draw: the necessity of working on a combined schedule with a partner and fulfilling their expectations as much as yours, the need for conciseness and absolute control over your expression, and so on. However, the rewards of comics writing surpass all the potential drawbacks, at least in the opinion of one who likes collaboration and craves a way to structure and rein in an unbridled imagination.

But an even more specific answer came to me during a conversation on a train.

At the end of May, Lisa Huberman came to Chicago for a visit. Lisa has been one of my best friends for twelve years and is a remarkably gifted writer herself. (She was just published in The Dramatist.) We were taking the Red Line up north and in between the rattle of the wheels I was describing the latest developments with my books when she asked during a natural pause in the telling the question which inspired this piece: “Why comics? What makes comics different and appealing?”

I told her about the book I finished two days before, Lucy Knisley’s Relish: My Life in the Kitchen.

The inner gatefold picture, one of the finest of this variety.

This is not exactly a review of Relish. In my humble opinion, the book is terrific, one of the most enjoyable pieces of graphic literature of the year, possibly the decade when we hit 2020. But there are plenty of full time critics who, given the book is a New York Times best seller, have produced essays, including an almost scathing piece in The Comics Journal which I found raised some good points but missed the mark completely in others. I’ll be taking some time respond to that, but mostly I want to describe what Relish is, which is not the simplest thing to describe.

Relish is first and foremost a book about food. It is a sonnet, an encomium, a celebration of the pleasures of eating, cooking, growing, even simply smelling food. Knisley takes us on a round-the-world culinary trip, describing the arts of shucking oysters, cheesemongering in gourmet food markets in New York and Chicago, attempting to bake your own version of the perfect Venetian croissant, and sampling unexpected delights in Mexico and Japan. Along the way, she muses on the inextinguishable joy of eating at the family table over even the finest restaurants, the psychological sides of craving, the pleasure of cooking for others, and the important association of food with memory. It’s akin to Michael Pollan’s work, but while Knisley is vocal about her support of local production and real ingredients, she is less concerned with ethics and the “how” of eating and more focused on how food is integral to personality.

Which is why Relish is also a unique autobiography. In the aforementioned Comics Journal review, Alex Deuben criticizes Knisley for not being “revealing” and saying little about herself and far less about her parents and the other figures whom she depicts throughout the book. His closing sentence is “If you’re looking for a book that tells you that Lucy Knisley is awesome and loves food, then Relish is for you, but if you’re looking for anything more, then unfortunately you’re out of luck.” I agree with Deuben up to a point: Relish is not a plunging examination of Knisley’s mind and soul, but in reading between the lines and under the surface, one interprets a more complex picture of Knisley, a not exactly flattering and golden one at that, which is indeed revelatory. Knisley depicts herself as a craver, a person easily irritated and driven to obsession (the croissant episode being a prime example), and full of longings so insatiable as to potentially never be satisfied…but who has the presence of mind to live a fulfilling and happy life in spite of this. She also hints at a family dynamic which may explain her parents’ divorce: her mother shares similar tendencies while her father is a more relaxed figure who possesses particular, results-oriented demands without the compulsion to work toward said results. Knisley rarely states any of the above barefaced, but in her painstakingly detailed analysis of that food-personality equation, the results are there, and they lend a serious layer to a book so light-hearted on the surface.

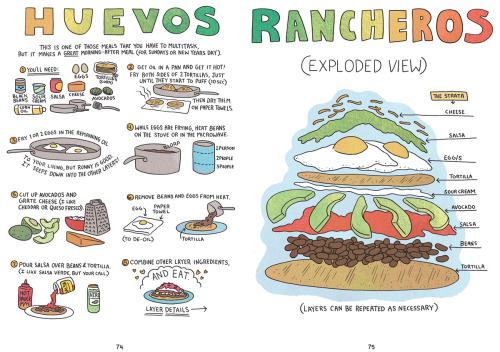

And to drive that point home, one must point out that Relish doubles as an illustrated cookbook, with Knisley sharing her favorite recipes, including homemade pickles, carbonara, sushi, chocolate chip cookies, and Shepard Fairey Pie (vegan and delicious-sounding), each recipe growing out of its chapter. (Again, Deuben fails to see this and criticizes the recipes as having nothing to do with the accompanying images and text, but he fails to account for the thematic throughlines: the one part where he is right is when Knisley uses her inability to bake those croissants (SERIOUSLY, THE CROISSANT EPISODE IS GIANT IN THIS BOOK) as an excuse to pass along her one alcohol-fueled concoction, a simple yet delectable sangria which indeed has nothing to do with the book, but can be forgiven as an indulgent moment in a saga of indulgence.)

Therefore, Relish is actually three different books rolled into one: philosophy, autobiography, and cookbook, and potentially it could have read as a mess. But these different strands are unified by the presence of Knisely’s illustrations, work with inviting line and imaginative color which stays consistently inventive throughout and eases the transitions between the seriousness and the fun to the point where the reader finds it impossible to separate the multiple ideas and themes being played with and see them as an equal, flowing piece.

And this is why I write comics.

It’s an old cliché among creative types that all of us have a great work of art in us waiting to get out. Cliches wouldn’t be clichés if they weren’t true at heart, and I personally believe everyone has a story to tell and a way to express it. But human beings are such astounding creatures; Walt Whitman’s “I contain multitudes” is one of the truest things ever said about our species. Any attempt to let the self out into the world has to recognize that the self is impossible to define in a sentence, and usually an entire book. So many disparate experiences and passions go into our beliefs, philosophies, and needs that to compartmentalize is almost to lie, to shed light on parts instead of the whole. But with the graphic novel, the unifying factor which makes our multitudes cohere and become intelligible to others is provided, and in a way which is not prohibitively disconcerting: a film of Relish would leap from one environment to the next with obvious visual differences, but Knisely’s art gives her story a uniform structure.

And once we have created this book, I believe it becomes easier to see in almost a Taoist sense how so much of existence is interrelated, converges in unexpected but understandable ways, and from there new books and new ideas come.

The possibilities of comics are almost endless in this sense. The combination of words and pictures in its maturity, and it is still evolving, might have opened the greatest storytelling frontiers since Cervantes and Shakespeare’s day, and books like Knisley’s point the way that I wish to follow.

I highly recommend Lucy Knisley’s web site and also her eight illustrations which tell the entire saga of Harry Potter.