Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, and he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every week, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

For my final column before the Academy Awards nominations are announced, I want you, fair readers, to imagine a Venn diagram. One circle is that fascinating genre, the Revisionist Western. The other circle is of films starring Jennifer Jason Leigh, who has never become a major star but has rewarded the cinema faithful with an fascinating career marked by great choices and performances. (If you haven’t seen Fast Times at Ridgemont High, then stop reading right now and instead watch that.) I’m going to start with a film in the intersection of those circles, then branch off into two films that occupy the other circles, all of which went into wide release this weekend…and I save the best for last.

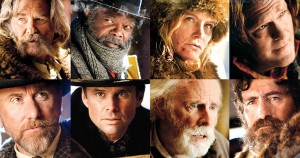

70 Millimeters of Darkness: The Hateful Eight

I have spent the past decade watching the exponential growth of my love for Quentin Tarantino as, starting with Death Proof, he made films that after the unwieldy mash-up of Kill Bill had a clear form and structure set to his singular logic. These were films full of brilliant writing, impressive scale, and actors having the time of their lives. They were great. The greatness has ended with a film that feels like the culmination of all Tarantino’s ambitions: The Hateful Eight.

Aesthetically, The Hateful Eight is the movie I now believe Tarantino dreamed of making since Death Proof: a film produced with all the magnificence of old-school Hollywood, complete with 70mm Super Panavision screening and in some parts of America the full road show experience with overture and intermission, but a film which also followed the tradition of his beloved grindhouse and exploitation cinema, with malingering, static stretches in between moments of provocation and shock. It’s a fascinating combination.

Thematically, Tarantino has embarked on something far more serious than his recent work. His last two films were crowd-pleasing revenge fantasies, but in The Hateful Eight, clearly drawing off the tensions in post-Ferguson America, Tarantino asks where the energy that fuels revenge comes from and reveals—I think correctly to a point—that the USA is a country built on a foundation of hatred. Using an unknown spot in the 1870s west as his backdrop, Tarantino gives us an all too real picture of how race, politics, philosophy, and money can divide us and provoke violence, and the only solution to these hatreds may be uniting to hate someone else. It is a film with no heroes and no one to positively identify with; a challenge to the viewer to look at the hatefulness within. I admire that.

I do not admire that The Hateful Eight seems to have lacked editing. Almost every scene that doesn’t involve gunplay goes on at least half a minute too long. Tarantino’s genius is on display in some scenes, especially Tim Roth’s monologue on justice and Samuel L. Jackson’s storytelling, but too often he slides past banal literalism, which would have suited the theme, into obviousness. And I really do not admire that the ultimate hatred in the movie, the one that determines the ending is the hatred and fear men have for women, especially intelligent women. I want to give Tarantino the benefit of the doubt that he intended to show the social devastation of misogyny, but he seems to relish the three hours of torture and victimizing and increasing weakness of Leigh’s Daisy Domergue—a woman who is as much a sinner as any of them but whose sin is rooted in DeConnick-style noncompliance with the social norm. Her treatment and her fate in a movie where every moment of violence registers hard pushed me to a point where I had a stomachache at the end of the film.

The Hateful Eight is not a bad movie. The cast is committed and excellent, with the aforementioned actors, Kurt Russell, and Channing Tatum (!) leaving lasting impressions. Robert Richardson’s cinematography is breathtaking, and using 70mm to create a proscenium style in the interiors is a clever idea. Ennio Morricone’s foreboding score suits it perfectly. The scenes right before the intermission and at the very end are the most shattering Tarantino has ever directed. And the level of vileness the action reaches is perversely demanding of respect. But it is a movie impossible to like, as the determination to show hatred results in that hatred overwhelming the movie to a degree where it becomes horrifyingly unwatchable or ultimately demonizing to the point that Tarantino’s theme is easily mistaken. People walked out of the screening I attended with an excitement, a joy in what they witnessed, that mystified me, glued to my chair in physical pain and hearing only the whirr of the projector and Roy Orbison’s haunting voice over the credits.

(A final note: in the second half of the movie, Tarantino uses songs from two other films, The Last House on the Left and The Fastest Guitar Alive. Think of those pictures put together and you have an idea of what you’re in for.)

The Gorgeous Pointlessness: The Revenant

If Robert Richardson’s cinematography is breathtaking, Emmanuel Lubezki is working at the highest powers that the art can grant an individual in The Revenant. Chivo, who has thrilled me to no end over the past years, has transcended a century of camera work. Shooting with natural light in Canada, America, and Argentina, Lubezki offers the most magical vistas, paintings of Remington and the Hudson River School coming to life before our eyes, with forests, fires on the plain, mountain ranges, and the Aurora Borealis depicted as if we were the first humans to ever look on them, and with such precise imagination that a viewer must be scanning every corner of the picture to see what is happening in the foreground and background. This unusual beauty extends to the fight scenes that bookend the film, scenes in which death is portrayed even more gruesomely and realistically than in Tarantino’s dark vision.

I want to take full pleasure in the above paragraph, but it only makes me sad, for Chivo has given us this offering in service of Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s worst film.

This is not a statement I make lightly. But The Revenant is worse than Inarritu’s two other giant-scale pictures, Babel and Birdman, which at least had stabs at ideas and actual characters. The Revenant, which is based “in part” (dangerous words) on a novel by Michael Funke, which itself was adapted from the true story of Hugh Glass, which was already the basis for Richard C. Sarafian’s 1971 Man in the Wilderness with Richard Harris and John Huston, is a film with no ideas in which all the people on screen are ciphers, not actual characters. Hugh Glass, left for dead after being mauled by a bear on an expedition in the 1820s, does nothing but track and trail people with help from his son, set out for revenge, and ultimately make a decision in the final scenes that feels completely pointless. Fitzgerald, his nemesis, is a self-serving capitalist with no other character traits. The Indian chief gets to make a big speech to French trappers about how the oppression of white men, but the screenplay by Inarritu and Mark E. Smith depicts Native Americans either as unstoppable threats to be feared or people easily brutalized. It is an overly simplistic film, but Inarritu’s grandeur and two and a half hour running time, padded by incomprehensible flashbacks and useless scenes (such as when Glass and an Indian ally he finds spend thirty seconds catching snowflakes on their tongues) attempt to make it high art, failing because there is nothing to back up such pretension. When scenes, such as the bear attack, that are meant to be riveting provoke only laughter from a packed house, something is going wrong.

The “nothing” includes the acting. Leonardo DiCaprio’s much-anticipated performance mainly consists of him running, fighting, squirming, and growling with almost no dialogue and nothing to engage our sympathies; it’s akin to watching a child playing at wilderness adventure. Tom Hardy, amazingly made ugly thanks to a faux-scalping and mounds of facial hair, gives himself a voice as incomprehensible as 75% of the cast (seriously, you can barely understand any of the dialogue) and never rises above cartoon villain, even when he has a “Quint and the Indianapolis” moment telling a story about finding God in a squirrel. Domhnall Gleeson projects long-suffering nobility, Will Poulter works hard to build a complex figure out of Hardy’s guilt-stricken, unwilling partner but is let down by the script, and the rest of the film is populated with nonentities.

The Revenant is a film I hate to recommend because it adds nothing to the cinema world. It is worth seeing once, on the big screen, to bask in Lubezki’s glow, but then should be quickly forgotten and peddled out only to give film students lessons in masterful cinematography.

Laughter and Tenderness: Anomalisa

But in the end, let us turn away from epics Westerns to animation running less than ninety minutes.

Charlie Kaufman has not made a film since his directorial debut Synecdoche, New York. Now, working with co-director Duke Johnson, he has given us the two-years-in-the-making Anomalisa, a film based on a staged radio play (which seems so completely Kaufman) that he wrote earlier this decade. In contrast to the scale of Synecdoche and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Anomalisa is a film in which fifty percent technically takes place in a single hotel room. There are three people in the cast. And the entire work is done in sophisticated stop-motion animation, with the characters designed with sharp lines running through their heads that make it seem like their faces could pop off and expose their true emotions.

But in this context, Kaufman works with giant themes. His work has been about the nature of love and existence, and Anomalisa probes the why behind those ideas. Why do we love? Why do we become attracted to people? Why do we value our existence as fully as we do? Kaufman find the answer to these questions in individuality: how we can be drawn to people with affinities which may make sense to no one else but perfect sense to us, and the concurrent danger of pushing our individuality so far that it turns into destructive egocentrism. Kaufman wisely leaves enough room for viewers to ponder their own points of view in conjunction with his own.

Kaufman’s script is reminiscent of Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter: terse, minimal, and full of variations on themes that never hit repetition (the supporting cast’s habit of repeating phrases and names), but at the same time recognizant of a giant world and the weight of history. It is poetic sparseness, and it is perfectly spoken by the weary, empathetic David Thewlis as the customer service guru Michael Stone and Leigh, so much more natural and freer than she is in The Hateful Eight, as Lisa, the woman whom everyone but Michael sees as ordinary and easily passed over. They play off each other as the two poles of individuality, Michael representing it as separating and Lisa as enriching and connecting, and the chemistry between Thewlis and Leigh s=even as voices is wonderful. A long sequence that begins with Lisa rhapsodizing over Cyndi Lauper and ends with a sex scene that, despite being between cartoon characters, is more realistic and tender than any sex scene this year is masterful. (If you ever wanted to see animated characters use toilets and have full frontal nude scenes, this is your chance.) It is also a very funny film full of visual jokes and surprising speeches: the movie takes place in Cincinnati, and one of the highlights is a rapturous monologue on that city’s chili.

There are two flaws in Anomalisa. The great character actor Tom Noonan voices everyone except Michael and Lisa and deliberately never alters his tone. This reflects Michael’s point of view as seeing the world as full of sameness and is occasionally hilarious, but it more often to me was awkward and annoying. And this short film contains some underdeveloped or poorly executed ideas, the key offender being a dream sequence of Michael meeting the hotel manager in a bizarre office—the sequence drags, ends confusingly, and momentarily engages with the animation style but quickly abandons such self-commentary. However, these can be accepted as part of Kaufman’s world-building and take nothing away from his complex ideas on human personality and connection. Anomalisa doesn’t offer a traditional happy ending but it leaves enough room for the perceptive viewer to find some sort of hope, an idea as valid as any presented by these Westerns.

Photos from Screenrant, Cultura Colectiva, Daily Caller, and Critics Roundup.