Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, but he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on either current pictures or important movies from the past.

In my last column, Alex and I discussed how the biopic is a genre the Academy always favors. It’s also a genre that’s hard to do well. There have been some outstanding examples (Amadeus, Lincoln, 12 Years a Slave) but I’m usually uninterested because I know how the story ends. When I go to movies, I want films that will unfold with drama and unpredictability, not like the connect-the-dots I adored as a child.

This year’s crop of biopics, however, has a twist to it. In the indie film version of the “Year of the Two Volcano Movies” and “Year of the Two Asteroid Movies,” 2014 turned out to be “Year of the Two British Scientist Movies,” and as an admitted Anglophile who loves well-made, intellectual English drama, I decided I needed to see them both.

Better Movie Without Science

On the one hand, The Theory of Everything is standard issue. Its Cliffs Notes depiction of the life of Stephen Hawking skimps so much on what makes him matter, presenting the most bare-bones scenes of him at work and giving little rationale for how his ideas evolved over time. It also, except for the final ten minutes and their terrible descent into the hokey, isn’t terrible. Oscar-winner James Marsh (Man on Wire) directs with the right touch of flair, using the full palette of the camera to good effect—the film is shot in a muted palette, but explodes with much more intense color for key scenes—and the screenplay is decent.

On the other hand, Everything is boosted by tremendous acting. Many biopics seem determined to present their subjects as figures of virtue or hellishness, with dramatic transformations from one to the other, but Stephen and Jane Hawking are portrayed as very ordinary people who grow, change, and find that what they wanted at 20 isn’t the same as what they need pushing 40. From their very first conversation, in which Stephen’s atheism is set against Jane’s devoutness, these two are established as having little in common and the gap between them only widens, but they also share an emotional bond that needs no reason. The parts of the film—the most effective—dealing with this tension depict adult maturation in a way I’ve rarely seen. If it hadn’t been a movie about Stephen Hawking, forced to shoehorn in details that really do not seem to interest the filmmakers (and again, if they had cut the unnecessary fantasy elements and montages in the last ten minutes), this would have been a superb picture.

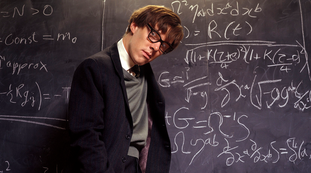

This character growth works because of Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones. Redmayne gets the showy part but he doesn’t exaggerate Stephen’s decline and the ways he moves, smiles, even blinks are remarkably realistic. More importantly, Redmayne captures an endearing emotional awkwardness. He is always blunt and sometimes thoughtless, but charming and sympathetic. Jones has the quieter part, but she brings a great interior war to the surface in little moments of tears, prayers, and contorted body parts, and always projects a will as strong as any action hero. Also leaving a terrific impression is Charlie Cox as a widowed church music director who befriends the Hawkings and finds himself in an unexpectedly difficult emotional situation. But this is Redmayne and Jones’s show all the way, and they both deserve Oscar nominations for this work.

Andrew Now Understands the Hype Over Benedict Cumberbatch

While there are several things to praise in The Theory of Everything, The Imitation Game may turn out to be the worst movie in major Oscar contention this year.

We hate to criticize a Chicago native who made good, but Graham Moore’s screenplay stinks. It awkwardly cuts back and forth between three time periods—Alan Turing’s school days in 1928, the Bletchley Park mission to break the Enigma code in 1939-1945, and 1951-52. The 1928 sequences are truly well-done (with a fine turn by Alex Lawther as the young Turing), but Bletchley Park is where we are for the bulk, and this part is full of poorly-developed characters, flat and repetitive dialogue, inexplicable tonal shifts, and plot elements that are introduced but never resolved. Alastair Dennison (Charles Dance), the commander of Bletchley Park, simply disappears halfway through the movie after being set up as the main antagonist, while Mark Strong, who looks almost fatherly as MI6 chief Stewart Menzies, comes across as a hero one moment, a terrifying figure the next, and shows up at the beginning of the 1951 sequences only to never come back. All of this is beyond frustrating.

The frustrations grow. Morton Tyldum is a superstar director in Norway, but his first English film is full of sloppy framing and awkward editing—and whenever he hits a slow spot, he throws in random ultra-CGI’d images of combat and bombings. The supporting cast has nothing to do; wasted above all is Matthew Goode, who was apparently told to just stand around looking and sounding like Cary Grant for a couple hours. Finally, the now-common concluding text crawl telling us what happened to people after the movie ended is a jumbled mess projected over a jumbled montage that aims for a triumphant tone but fails.

All this being said, there are two things I give my unqualified support to in The Imitation Game. One, it does a much better job than Everything to explain why Turing matters. Two, Benedict Cumberbatch is electrifying. Much like when I saw Kevin Spacey in American Beauty, I couldn’t believe an actor was taking such horrid material and giving the performance of a lifetime. Cumberbatch’s Turing is brilliant, arrogant, and full of lovelorn emotion which he slowly lets out little by little until the climax. It is a breathtaking piece of control, and he delivers the not-always-good lines and narration with a rich voice and a commanding presence (he even resembles the real Turing to a degree) both full of subtleties and coded meanings. The intimacy Cumberbatch creates makes him at his best in one-on-one scenes with Dance, Keira Knightley (who gives a terrific low-key performance as the great cryptographer Joan Clarke, which I doubly loved as an inspiring portrayal of women in science in a time when the world needs such figures), and Rory Kinnear. Indeed, there is one moment in the middle of the film, when Cumberbatch is explaining what “the imitation game” is to Kinnear, where the movie is forgotten and it seems the spirit of Alan Turing is simply talking to us. Such moments in cinema are rare and overwhelming, and almost make up for the horridness of the rest.

These two films are not great; heck, their level of “good” is questionable. But they’re both worth seeing before the Oscars, particularly if you’re a fan of the personalities involved, because they boast some of the best acting of the half-decade.