Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, but he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

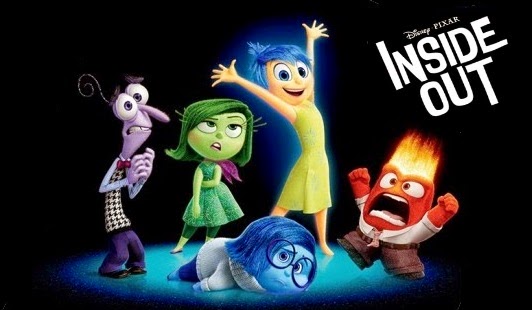

One of the most indelible memories of childhood moviegoing was twenty years ago, watching a cartoon the likes of which I had never seen before called Toy Story. Since that day in 1995, Pixar has given the world a gift of extraordinary all-ages films from studio chief John Lasseter, Brad Bird, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, and others that have redefined both the style and substance of modern filmmaking. However, Pixar post-2010 has fallen into a rut, mostly producing films of lesser quality. Inside Out, the new feature from Docter (who also helmed Monsters, Inc. and Up), is a sign that this trend is about to change.

The Dueling Forces That Drive Pixar

Inside Out was a cause for celebration in my mind even before its release, and to understand why requires a very brief look what I see as the dueling ambitions of Pixar.

On the one hand, Pixar unquestionably wants to not just push the envelope of animation, but send it falling over the cliff into a storm until it is ripped into confetti. This goes right back to Toy Story and the early films, in which the studio tested how far and how detailed computer animation can go. Watching the film-by-film progression is stunning, all the more so when thinking of how genuinely good those movies were. By the time of Finding Nemo in 2003, the animation was in an unprecedented place, and at this point Pixar, as an established brand, began developing original and almost unprecedented stories, fusing the Disney style with the aesthetics of not just Hayao Miyazaki, whom the studio chiefs worship, but also the great American independent lineage that stretches from the Hubleys to Richard Williams to Ralph Bakshi. The run from 2003 to 2009 that gave us Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Ratatouille, WALL-E, and Up was a series of unexpected and not obviously commercial plots (A rat becomes a chef? Two robots on a destroyed Earth? An old widower flies his house to the middle of South America?), remarkably intelligent screenplays, and breathtakingly executed animation, all with a sense of heart and wonder to charm even the most icily analytical critic.

Maybe I overstate the case, but I can remember seeing those films in cinemas and being filled with wonder and something close to rapture at how smart, funny, beautiful, and inspiring these movies could be.

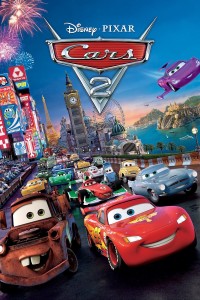

I left one picture out of that list above, because it speaks to Pixar’s other ambition: to be a blockbuster factory on par with Disney at its best.

The missing movie is, of course, Cars, lifelong automobile lover John Lasseter’s pet project. Though made from a place of great heart, Cars was an overly cartoony, less interesting film with a derivative plot and a great deal done in service to Larry the Cable Guy’s “wackiness.” This drop in Pixar quality didn’t matter, because they—and Disney—realized that talking, friendly-looking cars were a marketing dream. Cars raked in a fortune, and suddenly Pixar was developing films as properties that could tie in to past successes and attract an audience eager to pay to revisit characters and earn a mint from the accompanying merchandise. The ambitious Brave was an anomaly in a string of giant sequels, and while Toy Story 3 mixed some terrific comedy with a genuine tear-jerker of a plot, Cars 2 and Monsters University were two of the more pointless movies ever made. Watching these films come out, I realized that Pixar in the 2010s was losing its luster, especially with Disney’s own animation studio surging back to the forefront with the critical and commercial smashes of Tangled and Frozen.

Therefore, a highly unusual film such as Inside Out led me to conclude that Pixar had gone again in search of the magic, to make a film that would be both a giant hit and, more importantly, give audiences something they had never seen before.

The former aim is an open question for now, but they definitely succeeded with the latter.

The Genius and Emotions of Inside Out

Inside Out is a film with no anthropomorphism and nothing automatically marketable in sight. The film concerns itself with 11 year-old Riley Anderson–an average, very happy girl from Minnesota whose family moves to San Francisco–and even more specifically concerns itself with Riley’s emotions of Joy, Sadness, Fear, Disgust, and Anger, who “run” her mentality from their Headquarters. The tumult of the move causes an occurrence in Riley’s mind that flings Joy and Sadness from Headquarters, and the two end up on a tour of her consciousness while Fear, Disgust, and Anger try to hold things together. What the viewer sees is that Riley’s imagination, knowledge, and critical reasoning are all linked to her memories and the emotions that shape these memories, the whole combining to form her personality. This concept alone makes Inside Out a wise film; so often, intellect and emotion are portrayed as different ends of a scale (think Kirk and Spock), but this film demonstrates how they are inextricably linked in a way anyone, especially the target audience, can understand. However, the movie goes further.

The heart of the movie comes from a misunderstanding on the part of Joy. The emotions all get along well, but Joy has never understood why Sadness is there and what purpose she serves. The journey they take together results in Joy having a revelation as to why Sadness is necessary for the personality. I don’t want to give away too much of the plot, but the final conclusion of Inside Out is that people live a great life not when their existence is full of joy, but when they can be honest about their emotions and let those emotions emerge at the times they are needed. In a climate where so many movies define success as triumph and contentment, and reserve emotional complexity for more downbeat stories, the message of Inside Out is an outstanding one for an impressionable mind and heart.

Moreover, the ideas are perfectly executed in the animation and casting. Docter and co-director Ronnie Del Carmen create the most all-encompassing of Pixar’s universes. The real world is depicted with expected and ever-more-refined care and detail, but Riley’s head is a smorgasbord of styles, from the 1950s retro futurism-meets-Broadway musical (in the animators’ own words) of Headquarters to the grandiose color explosions of Imagination to the darkness of the Abyss (where obsolete memories are pushed to be forgotten) to my personal favorite, Abstract Reasoning, a world that owes a great debt to Chuck Jones’s most ambitious cartoons. The emotions themselves are rendered with some of Pixar’s most complex and beautiful designs ever; Docter conceived of the constantly active emotions as “a massive collection of energy” and their bodies constantly shift and sparkle. It delights the eye and boggles the brain as to how well they pulled it off. In addition, the visual palette is reflected in a whimsical and moving Michael Giacchino score that seems to use every instrument conceivable.

The animation, and the screenplay by Docter, Josh Cooley, and Meg LeFauve (who is now working on Captain Marvel, which is an exciting thought) is accompanied by a terrific voice cast. At the center of this cast is Amy Poehler, and anyone who doubts she is a national treasure will be convinced by her portrayal of Joy.

Poehler bursts with spirit, strength, and an irrepressible cheerfulness as Joy, but also knows when to rein her joyfulness in for the two most effective and moving scenes of the picture. One is the opening, when a newborn Riley opens her eyes, sees her parents, and makes Joy the very first emotion to be called into being. The other is Joy’s revelation about Sadness, which occurs when Joy accidentally lands in the Abyss and picks through a multitude of memories. No Pixar sequence will ever match the opening of Up in terms of making you weep, but this part of Inside Out runs a very close second. I don’t want to say much more…just watch the movie.

Poehler’s performance works in large part due to her interplay with Phyllis Smith, who is wonderful as Sadness, by turns so mopey she can’t even walk and very empathetic, with a drooping but strangely warm voice to match. (I also love their designs: they look like two 1950s liberal arts students, Joy the chic one with an Audrey Hepburn cut, Sadness the intellectual with owl glasses and turtleneck.) Lewis Black, Bill Hader, and Mindy Kaling are just as perfectly cast and provide some necessary light touches to the serious story. Richard Kind does his borscht belt best as an imaginary friend, and the rest of the cast is full of wonderful little turns from very welcome voices. A final mention must be given to Kaitlyn Dias, who excels as Riley, conveying all her different moods with conviction.

Riley is the reason I urge any reader with children, nieces and nephews, little cousins, or any youths in their charge to go see Inside Out. It is a work that fulfills its ambitions and offers something valuable to take away. And it restores Pixar to the forefront of innovative cartoon-making. AND it has the funniest closing sequence in the studio’s history.

Images from Fat Movie Guy, IMDB, Red Oak Junior High School, Subscene, and Chicago Now.