Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, but he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

Next week, there’s a movie opening in which James Spader takes on eight or nine lost creatures in a duel for the fate of humanity. I kid because I know Age of Ultron will rake in more than the entire Recorder staff will make in our lives 100 times over. Thinking about this sure thing, however, led me down one of my inquisitive rabbit holes. What in a movie attracts the mass audience to go see it? What is the nature of the blockbuster?

This article will, in a very brief space, try to pinpoint what makes a film not just a hit but a phenomenon, and this year’s Guinness Book of Records provides a fantastic case study by including a list of the ten highest-grossing films ever made when every movie is adjusted for inflation. As it turns out, exactly fifty years ago, 1965 is significant to our little project for two reasons. One, it marks a chronological dividing line, as five of the top ten were released before or during that year and five after, starting with a film which changed the nature of blockbusters forever. Two, it is the only year in which TWO movies were released that made the top ten. (Although their budgets were so high that neither was the most profitable of the year. That honor went to Thunderball, which provides us with another maxim. Never bet against 007.)

Without further ado…

The List

Some of these may surprise you…

- Gone With the Wind (1939)

- Avatar (2009)

- Star Wars (or, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, For All You Retconning Nitpickers) (1977)

- Titanic (1997)

- The Sound of Music (1965)

- E. T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

- The Ten Commandments (1956)

- Doctor Zhivago (1965)

- Jaws (1975)

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)

I have seen nine of these films (still haven’t made it all the way through The Sound of Music…and yes, readers, you can lambast me in the comments all you want), almost all of them multiple times. One may be my favorite film ever. I’m positive most of the people reading this have seen the majority of these as well. And in looking at this range of Disney, Spielberg, Cameron, and lots of fire and water, certain patterns emerge.

I have seen nine of these films (still haven’t made it all the way through The Sound of Music…and yes, readers, you can lambast me in the comments all you want), almost all of them multiple times. One may be my favorite film ever. I’m positive most of the people reading this have seen the majority of these as well. And in looking at this range of Disney, Spielberg, Cameron, and lots of fire and water, certain patterns emerge.

Common Cores of the Blockbuster

KEEP IT FAMILIAR OR KEEP IT SIMPLE: The mass audience wants a story they know just well enough to attract them, or a story they don’t know but can easily understand.

The Harris Poll recently determined that almost eighty years after it was published, Gone With the Wind is still the favorite book among Americans. Not only was it a mammoth best-seller, but it also had a basic plotline anybody could emotionally connect to on some level. We all haven’t lived through the Civil War (unless we’ve got time machines in the basement), but most people have been in situations of unrequited love and stressful romantic triangles/rectangles/other polygons. We so easily understand Scarlett and Rhett even when we don’t like them.

Moving on, several other films on the list were adapted from best-sellers, Nobel Prize winners, fairy tales, hit musicals, and the Harris Poll’s second-favorite book in America, the Bible. The original stories, meanwhile, have plot summaries that are beautiful in their simplicity. Forget Joseph Campbell. Star Wars comes straight out of Morphology of the Folktale: a farm boy teams up with a mentor, a good-hearted adventurer, and some magical creatures to save a princess. And there are few easier ideas to grasp than “lonely boy meets lonely alien and they become friends” or “total opposites fall in love on a boat that’s about to sink.”

STUFF THEIR EYES WITH WONDER: A sentence from my favorite passage of Ray Bradbury’s applies here. Well-conceived, well-directed visual spectacle is always a plus. James Cameron is of course the master of this: the sinking of the Titanic remains a triumph of an action sequence, and Pandora (and its accompanying 3-D technology) have not yet been equaled. Just as amazing in their own times and still breathtaking today are the burning of Atlanta, the parting of the Red Sea, and every frame of Star Wars.

A LITTLE ROMANCE GOES A LONG WAY: Turning back to my thoughts on plot summary, almost every film on this list has a love story near its center. (Even Star Wars had its hint, though that would be disproven in the future episodes.) Even if it’s not romantic love, these films turn around familial love (E.T.) or love of your people (The Ten Commandments). A writer cannot just toss protagonists into an action-packed maelstrom and expect audiences to care unless the protagonists have people they care about to drive them on.

The Three Outliers

Having said all this, there are some pictures here that raised further questions or didn’t quite fit into this neat little narrative.

Jaws may have the simplest story of them all and it is so simple it leaves room for little else. There’s no love story. There’s no striking visuals, in part due to Bruce the mechanical shark breaking down. But Spielberg and company hit all the perfect beats of a thriller, except with a great white shark as the malevolent force instead of an all too human nemesis, and it was made with everyone working at the height of their powers. Superior craftsmanship and one slightly unusual idea can carry a film a long way.

Jaws may have the simplest story of them all and it is so simple it leaves room for little else. There’s no love story. There’s no striking visuals, in part due to Bruce the mechanical shark breaking down. But Spielberg and company hit all the perfect beats of a thriller, except with a great white shark as the malevolent force instead of an all too human nemesis, and it was made with everyone working at the height of their powers. Superior craftsmanship and one slightly unusual idea can carry a film a long way.

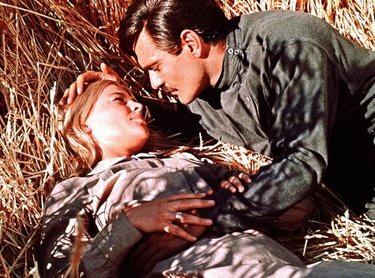

Doctor Zhivago, in turn, may be the greatest outlier on the list. This is possibly my favorite film ever, and it is epic-scaled in a way Jaws was not…but it definitely does not have the escapist feel the other films on this list do, even with the grand settings of World War I, the Russian Revolution, and that ice palace in the end. It is a film with an extremely passive hero who wants nothing but to be left alone to write poetry, but the forces of history create circumstances beyond his control (which also conveniently make him the fulcrum of a love triangle), and these forces, and the people who represent them, are mixtures of good and bad qualities, making deciding who’s right and wrong hard. So to recap: protagonist with little agency and resources caught in a complex, gigantic world, and whose one true moment of decision and action terminates the story. It sounds too much like real life to almost be bearable, and sometimes when I’m reveling in this film I’m astounded it was such a smash. And I’m glad for that.

Doctor Zhivago, in turn, may be the greatest outlier on the list. This is possibly my favorite film ever, and it is epic-scaled in a way Jaws was not…but it definitely does not have the escapist feel the other films on this list do, even with the grand settings of World War I, the Russian Revolution, and that ice palace in the end. It is a film with an extremely passive hero who wants nothing but to be left alone to write poetry, but the forces of history create circumstances beyond his control (which also conveniently make him the fulcrum of a love triangle), and these forces, and the people who represent them, are mixtures of good and bad qualities, making deciding who’s right and wrong hard. So to recap: protagonist with little agency and resources caught in a complex, gigantic world, and whose one true moment of decision and action terminates the story. It sounds too much like real life to almost be bearable, and sometimes when I’m reveling in this film I’m astounded it was such a smash. And I’m glad for that.

![]() Avatar, on the other hand, is still a marvel of cinematic possibility, but it’s also the most forgettable film on this list. The recent news of sequels has generated zero enthusiasm, because James Cameron invested himself so much in 3-D and the future of effects that he created the most hackneyed, uninteresting characters and story possible. The only lines and beats I remember are the most ridiculously bad ones, and the emotions are never engaged. It’s a Cinerama Holiday for the 21st century, a wonderful way to show off the new technology, but a total bore as a movie, which is what matters most.

Avatar, on the other hand, is still a marvel of cinematic possibility, but it’s also the most forgettable film on this list. The recent news of sequels has generated zero enthusiasm, because James Cameron invested himself so much in 3-D and the future of effects that he created the most hackneyed, uninteresting characters and story possible. The only lines and beats I remember are the most ridiculously bad ones, and the emotions are never engaged. It’s a Cinerama Holiday for the 21st century, a wonderful way to show off the new technology, but a total bore as a movie, which is what matters most.

The Conclusion

However, Avatar did have Pandora the way Jaws had the shark and the other eight movies had what made them special. And if there is one unifying element to the global blockbuster, I believe in the end that it’s having great talent giving an audience an experience they could never imagine having themselves. We can’t be present at historical cataclysms, and we in all likelihood won’t fight sea beasts, meet aliens (sometimes on other planets), or have romances that get written about with poetry that never finds its way to the gossip column. We probably won’t get superpowers or robot suits or magic hammers and save the world either. But movies give us the sensation of experiencing such things happening, and when made by people who care about every last detail, we may, by proxy, catch some of the emotion and excitement of such an experience within our own breasts.

And that’s why we love movies.

Photos from Vanity Fair, Huffington Post, ScreenRant, Midwest Texan, and 365ThingsAustin.