Andrew Rostan was a film student before he realized that making comics was his horrible destiny, but he’s never shaken his love of cinema. Every two weeks, he’ll opine on current pictures or important movies from the past.

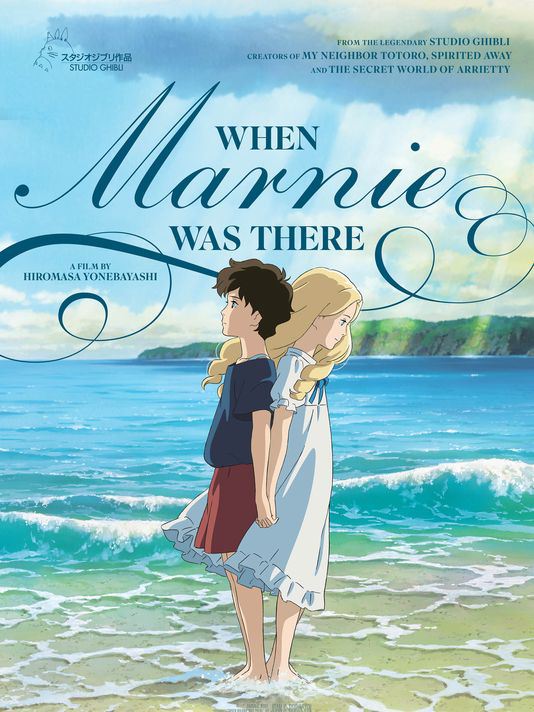

Last August, one month after they released their twentieth feature film, Studio Ghibli announced they would be taking a hiatus in the wake of Hayao Miyazaki’s retirement. Miyazaki has insisted that the studio will go on without him helming features, but this did not stop many fans from fretting that one of the most exceptional production companies of all time is done for. I’m inclined to believe Miyazaki, but if Ghibli indeed shutters for good, that twentieth film, Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s When Marnie Was There, which Disney has now released in the United States, would be a beautiful and fitting finale.

What Made Studio Ghibli Magic

Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata worked together for decades before founding Studio Ghibli in 1985. Their career trajectories were similar to those of Steven Spielberg, who began his career making commercial television; Miyazaki and Takahata were in charge of Lupin III, and Miyazaki’s directorial debut was a Lupin movie, The Castle of Cagliostro (which John Lasseter and other Pixarians have cited as a major influence). Miyazaki and Takahata’s years of apprenticeship and analysis gave them a thorough knowledge of how to tell stories for the general public. Once they were able to fully incorporate their ambitions and points of view, the results were instantly special.

For example, my personal first exposure to Studio Ghibli was the movie that gave them their own Mickey Mouse figurehead: Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro. My ten year-old self already knew this film was very different from the Disney movies I ate up. There were no princesses, no songs, and the movie felt much more deliberately written and differently paced. However, I fell in love with the movie and watched it over and over, and when I was in high school I discovered Princess Mononoke (which is still one of my favorite movies of all time) and other Ghibli films that were not necessarily for children only. I was hooked for life.

For example, my personal first exposure to Studio Ghibli was the movie that gave them their own Mickey Mouse figurehead: Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro. My ten year-old self already knew this film was very different from the Disney movies I ate up. There were no princesses, no songs, and the movie felt much more deliberately written and differently paced. However, I fell in love with the movie and watched it over and over, and when I was in high school I discovered Princess Mononoke (which is still one of my favorite movies of all time) and other Ghibli films that were not necessarily for children only. I was hooked for life.

What made these and the other Ghibli movies remarkable was a combination of characteristics, of which I can boil down three for this column. First, the traditional 2-D animation itself increasingly stands out in a computer-dominated cartoon world, and provides something to treasure for those who appreciate the time and care that goes into 2-D. But beyond the 2-D stylings, Miyazaki’s work was special. Disney animation at its best, particularly during the Renaissance years, possesses a flowing and easy quality (think of the dance in Beauty and the Beast and Ariel’s swimming) but also a placidness suitable for fairy tales. Anime carries a greater sense of action and intensity but also a manga-influenced static quality (as in the annoying fight scenes in Dragon Ball Z). Miyazaki, Takahata, and their successors combined the elaborate settings and ease of movement found in Disney with the intensity of anime: when characters in Ghibli films move, we can feel the wind around them and the weight and pressure with every action.

Second, the reference above to fairy tales was a deliberate one. Studio Ghibli’s films are infused with magic, talking animals, and otherworldly domains, all designed to fill our eyes with wonder, but they are decidedly not fairy tales and as such feel no need to be beholden to a specifically childish audience. Some films have specifically contemporary settings, and all of them reflect modern points of view while not being specifically tied to modernity. These are movies that will age extremely well.

Third and last, Takahata (as in his masterpiece Grave of the Fireflies), Miyazaki, and their brethren put women in the center of their movies, but not as uninteresting princess figures. These women are inspirational heroines, be they San/Mononoke, Kiki the witch, Sophie in Howl’s Moving Castle (who displays fiery strength as a young and old woman), or arguably Ghibli’s best heroine, the courageous ten year-old Chihiro in Spirited Away. These are protagonists whose adventures I will watch over and over again. This was a deliberate choice on Miyazaki’s part, and a great one considering that in the 1980s (in part because of no internet) there was not so loud a necessary outcry for a strong female presence in films as there is now. As Miyazaki himself said, his leads were “brave, self-sufficient girls that don’t think twice about fighting for what they believe in with all their heart. They’ll need a friend or a supporter but never a savior.” (If only more directors took this as an axiom.)

All three of these qualities—gorgeous art, a bit of magic, and great female characters—are on display in a film Miyazaki did not write or direct but masterfully closes out this chapter of the studio.

When Marnie Was There: Childhood’s End and Powerful Beginnings

Hiromasa Yonebayashi, a key animator on several Miyazaki films who also directed The Secret World of Arrietty for Ghibli, adapted When Marnie Was There from British author Joan G. Robinson’s 1967 novel. The film tells the story of Anna, a shy, lonely, asthmatic twelve year-old, whose mother sends her to stay with family for the summer in a seaside town in hopes that her health and spirits will improve. A terrific artist who is too nervous to show her work, Anna becomes obsessed with a seemingly abandoned mansion on the coastline she frequently sketches. One night she rows to the mansion and meets Marnie, a girl her own age who lives there. A deep, tender friendship arises even though Anna is clearly conscious that there is something unreal about Marnie. What that unreal quality is, and how Anna and Marnie are truly connected, tie into an ending that sees a transformed Anna take her first steps into maturity and personal happiness.

Hiromasa Yonebayashi, a key animator on several Miyazaki films who also directed The Secret World of Arrietty for Ghibli, adapted When Marnie Was There from British author Joan G. Robinson’s 1967 novel. The film tells the story of Anna, a shy, lonely, asthmatic twelve year-old, whose mother sends her to stay with family for the summer in a seaside town in hopes that her health and spirits will improve. A terrific artist who is too nervous to show her work, Anna becomes obsessed with a seemingly abandoned mansion on the coastline she frequently sketches. One night she rows to the mansion and meets Marnie, a girl her own age who lives there. A deep, tender friendship arises even though Anna is clearly conscious that there is something unreal about Marnie. What that unreal quality is, and how Anna and Marnie are truly connected, tie into an ending that sees a transformed Anna take her first steps into maturity and personal happiness.

If this is all there was to When Marnie Was There, then it would still be an exceptional picture. The majority of “coming of age” movies, from The 400 Blows to Boyhood, concern young men, and the Ghibli tendency to put women at the center serves this film refreshingly well. Anna and Marnie’s dreams, fears, slightly hyperbolic emotions, and occasional unthinking cruelty (one piercing scene has Anna call another local girl attempting to befriend her a fat pig) are all recognizable traits in those on the threshold of adolescence, and the film hits these emotional beats with honesty.

However, When Marnie Was There goes further and touchingly, realistically depicts Anna as suffering from depression. In the opening scenes her mother describes her as having “an ordinary face” that never betrays emotion, and for most of the movie Anna keeps this ordinariness, showing nothing and hiding herself from others, while sparse and effective voiceover reveals a constant monologue of self-hatred in her mind, phrased so simply that we believe how she has decided she is worthless. While the film offers a trigger for Anna’s depression, it resists a pop psychology approach and portrays the other characters in a way that classifies the emotional state as something natural. Further, the ending does not suggest that Anna has miraculously cured herself of negative feelings, rather that she has found herself to be capable of successfully dealing with them.

This plot doesn’t immediately suggest itself to animation; with the exception of a single third-act dream sequence, everything in here could have been shot live-action. What makes animation the necessary format for the storytelling is how Yonebayashi and his crew use it to reflect Anna’s giant-sized imagination and moods. The film reflects the grand scale of her mental state with lavish settings, carefully-used chiaroscuro, and bold, bright colors. The animation invites a younger audience into the complexities of the story, and further entrances a slightly older audience with the carefulness (which never gets formulaic) of its composition.

What ultimately makes When Marnie Was There a fitting climax for at least this phase of Studio Ghibli is the resolution between the art and the story. The film ends with Anna moving away from a fantasy world and into a reality where she sees herself and her future more clearly—where she will grow up—but it is a reality she did not perceive without the lessons learned in the fantasy world. Studio Ghibli’s ideal audience will continually grow older, but hopefully they will have learned lessons of their own from these films, and pass both lessons and films on to their children.

What ultimately makes When Marnie Was There a fitting climax for at least this phase of Studio Ghibli is the resolution between the art and the story. The film ends with Anna moving away from a fantasy world and into a reality where she sees herself and her future more clearly—where she will grow up—but it is a reality she did not perceive without the lessons learned in the fantasy world. Studio Ghibli’s ideal audience will continually grow older, but hopefully they will have learned lessons of their own from these films, and pass both lessons and films on to their children.

As a final note, GKIDS, the American distributor, provides an excellent voice cast as we have come to expect for Studio Ghibli releases. The English dub includes several actors who are always welcome, including Geena Davis as Anna’s mother and John C. Reilly lightening the tone as Anna’s host, but is definitely highlighted by the two leads, Hailee Steinfeld as the introspective, searching Anna, and Kiernan Shipka as the ethereal Marnie.

Images from Laughing Squid, Otherwhere, South China Morning Post, and rogerebert.com