Last week, Alex wrote an enlightening article about the traditional portrayal of Africa in Western Cinema here. The impetus of the piece was the arrival of the film Beasts of No Nation, adapted and directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga from the novel of the same name by Uzodinma Iweala. It’d be a lie to say that many of Alex’s thoughts and observations about the Africa of Western cinema didn’t color my reading of the film, but as with all good writing, it helped me to take notice of several things that might have been missed.

What was unmistakable to me, however, is the fact that Beasts of No Nation, in spite of its ambitions, fails to succeed on several different fronts. It is not without merit – but there’s a great deal missing that could have made this a great movie instead of another mediocre portrayal of an often-overlooked region of the world.

A Problem of Portrayal

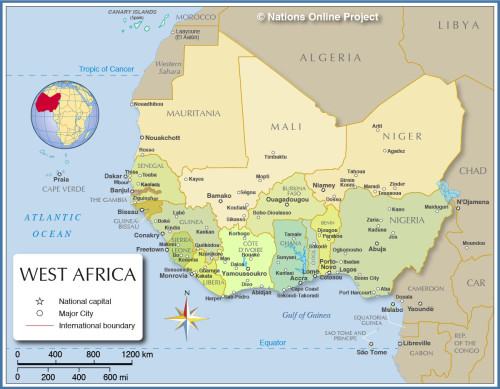

Beasts of No Nation is not set in any specific country (though it’s widely assumed to be Iweala’s native Nigeria in the book), and that factor, in my opinion, doesn’t do the movie any favors. It seems to be an attempt to turn the events of the film into that of a universal story, one that could apply to dozens of war-torn African countries. That’s an effective concept when applied to loose subjects relating to culture (i.e. Her is set in the near future, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is an unidentified small town, etc.), but smacks of over-generalization when applied to countries with as rich and diverse a tradition as those of Africa.

Colonialism has seemingly forever divided thousands of individual tribes into a number of states, republics, and territories with little or no meaning to the denizens of the state-drawn lines. It’s understandable of what they’re trying to portray by calling the members of the child army “beasts of no nation”, but something is off. The efforts to keep the country of discussion anonymous seems to say that this is a conflict that happens all over Africa. Shots of the main character, Agu, running into the bush. “Tribal garb” worn by the boys of the Native Defense Force. War-torn cities and small towns. The berets and devices worn as self-aggrandizing affectations by the generals of filsm like Last King of Scotland or Blood Diamond. These aren’t tokens of Africa as an actual place – these are tokens of the Western conception of Africa as a brutal, blood-soaked backwater populated by thugs and aggressors.

This is not to denigrate the experiences of countries like South Sudan, Rwanda, Nigeria, the D.R.C., and others – these are real world problems. However, it is a patronizing gesture that ignores the fact that many or most countries are quite modernized – the next portrayal of Nairobi as a city on par with any Western city in Western cinema will be a first, as far as I’m aware. (Feel free to enlighten me in the comment section below if I’m wrong)

Edmund Said wrote a great deal about Orientalism, the idea that the Western world glorifies and makes exotic other cultures – primarily Asia and the Middle East. That same concept is at work here, right from the very start. The title credits roll in painted brushstrokes that look as though they came from some simple children’s book about ‘the Dark Continent’. An old woman is called a “witch” by the local boys – an unsettling accusation not because of her turn in the plot, but because it feels like something uttered over and over again in Hollywood movies. These aren’t honest examples of a real country – the whole thing is a fictionalized sketch of an outdated idea.

What’s more, by painting these characters as symbols of the overt problems of Africa turns them into daguerreotypes of a notion of Africa and only heightens the fact that this is a work of fiction. These could be any of a hundred thousand small boys in any African country. That’s a sobering thought – and yet, in this film, it results in a sense of detachment that never allows for a true connection to the people of the story.

A Problem of Story

That lack of connection to the characters of the film isn’t solely the result of antiquated notions of Africa. It’s also the result of bad cinematic storytelling. On the surface, it should be relatively simple to tell the story of Agu’s descent into the hells of war upon his abduction. (Well, it’s actually not that simple, or more people would make movies) Even a poorly-conceived and culturally tone-deaf work can tell a great story. After all, moviegoers did pay money to see dreck like Invictus and The Imitation Game.

And yet, there’s something missing in the story-telling. The film’s best moments are in the early going, where we see Agu’s family life: his brother obsessively working out at he tries to win the affections of a local girl; Agu and his friends trying to sell a screenless TV as ‘an imagination TV’ where they act out the stories; a church scene that doesn’t completely patronize its subjects. A relationship is allowed to form, where the viewer can connect to Agu as a young boy.

And then, the war happens. It’s out of nowhere, which might be true in real life, but for a story like this to develop, there needs to be more tension built. There are indications that Fukunaga has tried this (lines like ‘we live in a buffer zone’), but the efforts are too simple to convey a sense of growing dread. I say simple and not subtle, which is what Fukunaga seems to be going for; it’s like if Da Vinci drew a halo above Jesus in “The Last Supper”.

Because of the abruptness with which Agu’s world falls apart, it’s more shocking than tragic. The ensuing scenes are rote and would normally be effective, yet there’s no time for reflection – Fukunaga speeds on past as if he’s in a hurry to get to the next part of the story.

That comes in the form of Idris Elba’s Commandant, a towering figure of seductive brutality – at least, that’s what Elba seems to be trying to convey. He moves with a swagger and speaks in a slow, measured tone. This isn’t wild overacting – it’s careful and precise. In many other films, this would be a rich character full of psychological depths to be mined, an exploration into the nature of evil. Unfortunately, there are no such depths given to the Commandant. We know that he used drugs and employs rape as a measure of manipulative control. We know that he lusts for power and will do anything to keep it. He seems aware of the brutality of what he’s committing, but we never know why he does what he does. Such an approach works if you’re dealing with a character like Emperor Palpatine, but not when you’re trying to create an allegorical narrative about child soldiers in the modern world.

The war scenes lack a brutality as well – we’re made to feel horrible because these are children walking into battle. We’re told that Agu has done terrible things – at the end of the film, he literally says as much. And yet, in only a few instances do we see him committing atrocities. The most brutal is the first time he kills a man, at the behest of the Commandant, another earnestly affecting moment. And yet, the after-effects are rushed through, glossed over because the film feels a need to keep moving.

That would be fine if the overall pace didn’t feel so glacial, a result of the film’s need to drag through long stretches of dialogue that add little to the proceedings. Fukunaga’s script seems to believe that it needs three pages of dialogue when one would suffice, and this makes for a lot of bathroom breaks when the narrative has ground to a halt; you’re not missing anything.

The climax of the film doesn’t feel earned, as Agu and the rest of the boys abandon the Commandant in favor of surrender. While the image of the Commandant mindlessly bellowing orders at nobody makes for a compelling image, it’s not accompanied by any sense of victory or relief. Rather, it’s as though Fukunaga has given up on trying to convey any idea of finality to the boy’s actions and instead just needs them to get to the next encampment. This is a shame, because the haunted look of doubt in Elba’s eyes feels as though it should be earned.

The resulting film is a mixed bag. It’s certainly very pretty, and Elba does give a performance that would make up for many failings of the film, were it to be backed by even a remote sense of psychological justification. Instead, what we get is another product rolling off the Netflix assembly line, the latest text in an ongoing failure of Western cinema to accurately portray the countries of an entire continent with anything resembling humanistic reality.