“How few know even the names of the men who design and execute the work and in whose care the public safety is placed. How vigilant and resourceful they must be is little appreciated by the passengers who are almost lifted as they ride.”

-M. K. Trumbull, Engineer of Track Elevation of the City of Chicago, 1908

The 1890 census confirmed Chicago had become the second largest city in the United States. Driven by immigration, the population had more than doubled in 10 years. 41 percent of residents were born in foreign countries. The Civil War, ending 25 years before, vaulted the geographically northern Chicago past traditional rivals St. Louis and Cincinnati as the Western hub of rail transportation and manufacturing. By 1889, thousands of trains were entering and leaving the city every day. More than 2,000 miles of track ran directly through Chicago neighborhoods, all at ground level.

Rapidly increasing population made the unending flow of trains a dangerous nuisance. One study found that, between 1889 and 1893, 1,700 people were killed in grade crossing accidents. In 1899, one out of every 220 people who died in Chicago was struck and killed by a train at a pedestrian crossing.

Viaducts across busy intersections were the first solution. Approaches ran up to half a mile long and any business owner unlucky enough to be located on an approach found themselves walled off by a slowly ascending path. The railroads were reluctant to build viaducts and the city faced frequent court battles. Citizens were stuck patiently waiting for trains to pass.

That patience quickly waned. By 1892, rail barons yearned for the days of low cost viaducts. Growing support for city-wide track elevation presaged huge construction costs. Preparing for the World’s Columbian Exposition, in May 1892 the city council passed an ordinance requiring the Illinois Central elevate their tracks from 51st St. to 67th St. In under a year, at a cost of two million dollars, the 2oo foot wide railbed was raised 18 feet into the air.

Emboldened by this success, the 1893 city council passed a general ordinance requiring the elimination of all grade level crossings in Chicago within 6 years. The railroads did not co-operate, claiming tracks could not be elevated in time. The ordinance didn’t specify how the projects would be funded, and the city initially lacked the legal authority and political will to strong-arm the railroads.

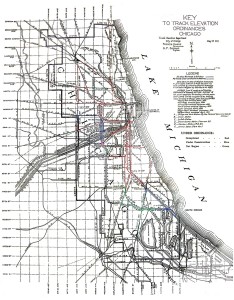

Eventually, the city council surveyed the lines running through Chicago, and passed specific ordinances targeting high traffic areas. Public opinion supported wholesale track elevation, mayors and aldermen made it a part of their campaigns, and some railroads worked with the city to pass more palatable ordinances. If railroads resisted, the city council threatened to revoke their right of way. In the next 17 years, 42 ordinances were passed. Tracks passing through wealthy areas were the first to be elevated and public pressure continued to grow. After a series of deaths in 1900, residents of Humboldt Park Blvd threatened to tear up the Bloomingdale Line (now the 606) if it was not elevated.

The elevation of the Chicago railroads was an engineering marvel. The Commissioner of Public Works allowed four consecutive streets to be blocked, so the completion of each ordinance took place in multiple stages. Remarkably, the railroads maintained their schedules throughout track elevation, sending trains over temporary tracks, or elevating tracks one at a time.

The ordinances were a fiscal triumph for the city. Construction costs were paid in full by the railroads. The city paid for damages to property resulting from track elevation, but most elevation ordinances required railroads to deposit a lump sum in the city treasury to account for these payments. By 1911, the estimated cost of track elevation was more than $66 million. Adjusting for inflation, the railroads had spent a total of $1.6 billion, the modern equivalent of building two Sears Towers. The city had spent a half-million dollars, less than one percent of the total cost.

As time passed, rail companies became more eager to elevate their tracks. It was a public relations boon, and trains were able to race more quickly through the city. Grade crossing accidents decreased dramatically, and with them, liability payouts shrank. In 1909, there were 96 grade crossing accidents, a 67% decrease in the span of 10 years.

When the United States joined World War 1 in 1917, the American government took control of the railroads and track elevation didn’t resume until 1924. The last elevation ordinance was passed in 1930 and was completed two years later. In January of 1938, the Committee on Track Elevation, which had overseen and guided all track elevation in Chicago, was disbanded. The railroads became unable to independently finance track elevation and the age of the automobile was well underway.