Welcome to “Recorded Conversations,” an occasional feature where all the Addison Recorder editors contribute their thoughts about a question, idea, or prompt. Everyone will chime in, and then we see where the conversation wanders. After the annual pop culture festival that is San Diego Comic Con, and shortly before fall semester starts at universities, J. Michael Bestul has posed this quandary:

Question: You’re teaching a class in popular culture, literature, or the like. As part of your curriculum, you need to incorporate one graphic novel or comic book series, and only one. Which one do you use, and why?

—

Answering this question was rather easy. There are four graphic novels which have surpassed the level of merely “inspirational” for me, and then it became a process-of-elimination game.

Jeff Smith’s Bone, which I have written about before, is at 1,332 pages—and every one of them densely packed—too long for this purpose. As much as I love Fun Home, Alison Bechdel’s work increasingly tips the balance in favor of words over pictures when they should be ideally equal. And Craig Thompson’s Blankets, even though it is the only comic which has ever made me weep, got crossed off for an odd reason. Even though Thompson’s illustrations are of the highest aesthetic caliber, I realized that except in a few places (the breathtaking, I’m trembling just thinking about it image of Craig and Raina’s bodies fused together, for example), the pictures and design augment the impact the reader feels as opposed to being in a symbiotic relationship with the story to create that impact.

(The same goes for Ray Fawkes’s breathtaking One Soul, which I recently finished and highly recommend.)

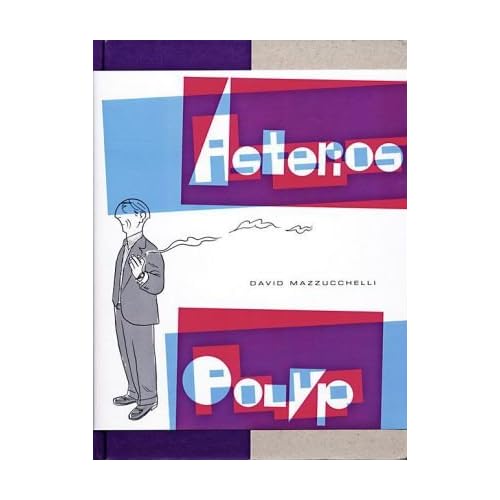

In comparison to these books, Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli revels in displaying all that the graphic novel is capable of, when not going farther and actually pushing the boundaries.

Every few pages, and sometimes in the same panel, Mazzucchelli will alter the paneling method, the color scheme, even the types of lines he is using to draw, creating a work which is as much a master class on how much variety lies in comics aesthetic and practice as Scott McCloud’s non-fiction titles. (Even Thompson sticks to the traditional one-panel-after-another form.) More importantly, Mazzucchelli is not showing off with this array of choices: every time his drawing and layout undergo a stylistic shift, it accompanies a change of scene and tone in the story; to take only one example, when Asterios and Hana have an argument, curvy florid red lines fill half a very detailed panel and blur into sharp geometric blue lines, reflecting the emotional distance between them. His words and pictures complement each other in a way very few texts in the medium have ever achieved.

But Asterios Polyp is more than a technical marvel. Mazzucchelli also tells a profound and gripping story laden with philosophical and romantic themes, and tells it with all the skill of a great novelist. He ties together multiple plotlines and uses recurring details in ways which make one want to immediately start the book over once finished. Best of all, the storytelling feels impossible without the illustrations. I cannot spoil anything, and do not even wish to talk about the plot to any extent. I will say that on the very first pages, a scene occurs which grows more and more laden with meaning as the reader discovers the many facets of Asterios. The scene’s significance could have been described with words alone, but I doubt this possibility…and even if it could have, it would have been far more difficult and hard to convey without Mazzucchelli’s well-chosen, ultimately heartbreaking imagery.

Asterios Polyp combines superb storytelling and pictorial artistry of the most innovative sort, and does so in a way which displays how words and pictures can work together in the best ways and not merely sit side by side. If I had to teach one graphic novel, pick only one which could encapsulate all that is wonderful and possible with the medium, it would be Asterios Polyp.

—

Read the responses from the other editors, J., Bean, and Travis, as they are published throughout today