Edgar Degas was the odd man out of the Impressionists. He exhibited with them as a reaction to the Salon and the French art establishment and shared many of their qualities, but he detested their experimentalism, plein air, and preference to create in the moment; his carefully composed and structured, mostly interior canvases were to the other Impressionists like a Damien Hirst in a field of Rembrandts.

He was also a priggish, reactionary, anti-Dreyfus man who didn’t date because he thought an artist should have no personal life. Fun times with Edgar!

But he was no less a genius, and the current miniature exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, Degas: At the Track, On the Stage is an ideal reflection of his prowess.

Two Masterpieces

The exhibition, as one would expect, features several paintings from Degas’s immortal cycle of ballet dancers and Paris theatrical life, including an attention-getting work from 1876, Cafe Concert, in which the stage is in the background and the eating, drinking, gossiping audience takes the fore. However, the Art Institute has chosen to highlight two works in particular which offer striking rewards for the careful observer.

Degas had a passion for sculpting but mostly kept it secret: his one exhibition of a sculpture in 1881 provoked the sort of critical reaction reserved for mindless special effects-driven films today. When Degas died in 1917, his heirs were surprised when they found 150 sculptures. A few of these are now on display in the Art Institute, including that provocative piece from 1881, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen.

Little Dancer is an arresting work. a bronze casting of Belgian ballet student Marie van Goethem which remains clad in a hair ribbon and dress of actual cloth and muslim selected by Degas. (It was originally displayed with a wig of real hair to match.) The worn material and aging of the statue have improved its already considerable beauty; they suggest the physical toll of living an active, disciplined life, and make visually manifest the interior wear of the body. However, the youthful clothing and the small smile on the dancer’s face simultaneously remind us this is a pure, excited child.

Degas’s work went beyond dancing, as the At the Track in the exhibition title implies. He had a similar fascination for horse racing, especially the steeplechases that had grown popular in Paris. In 1866, before his break with the Salon, he exhibited Scene From the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey, a depiction of a rider taking a tumble at an obstacle. Degas was not satisfied with the painting and spent almost three decades revising it, performing all sorts of art surgery on it from obscuring the position of the other horses’ legs to adding more jockeys. The final version clearly shows the effects of alterations, but it is a riveting and unusual scene. Degas’s jockey, his body limp and twisted against a background of pristine equestrian grace and stillness worthy of a Muybridge photograph, is as poetic an image as his ballet dancers.

Degas’s work went beyond dancing, as the At the Track in the exhibition title implies. He had a similar fascination for horse racing, especially the steeplechases that had grown popular in Paris. In 1866, before his break with the Salon, he exhibited Scene From the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey, a depiction of a rider taking a tumble at an obstacle. Degas was not satisfied with the painting and spent almost three decades revising it, performing all sorts of art surgery on it from obscuring the position of the other horses’ legs to adding more jockeys. The final version clearly shows the effects of alterations, but it is a riveting and unusual scene. Degas’s jockey, his body limp and twisted against a background of pristine equestrian grace and stillness worthy of a Muybridge photograph, is as poetic an image as his ballet dancers.

One Surprise

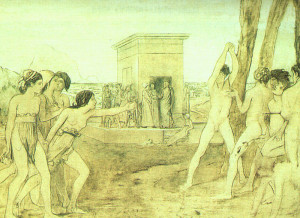

While perusing the exhibition, I encountered a study for a painting that was as startling and equally spellbinding to me as the steeplechase works. Young Spartan Girls Challenging Boys was created in 1860, when Degas was 26 and determined to be a history painter. The painting, a mix of creams and whites fitting to the classical Grecian setting, shows exactly what the title promises, with physically imposing, naked teenage girls issuing an athletic challenge to their equally nude male counterparts, but it is how Degas stages the scene that gains one’s attention. The women are composed almost in a wall as a united front of friends, while the men are scattered, lackadaisical, looking like pushovers in comparison, and on both sides one person is looking at another in their group with a sweet longing recognizable in any teenage crush. The psychological and sexual overtones in the painting make it clear that there is a singular creativity at work, and looks ahead to the decades to come.

While perusing the exhibition, I encountered a study for a painting that was as startling and equally spellbinding to me as the steeplechase works. Young Spartan Girls Challenging Boys was created in 1860, when Degas was 26 and determined to be a history painter. The painting, a mix of creams and whites fitting to the classical Grecian setting, shows exactly what the title promises, with physically imposing, naked teenage girls issuing an athletic challenge to their equally nude male counterparts, but it is how Degas stages the scene that gains one’s attention. The women are composed almost in a wall as a united front of friends, while the men are scattered, lackadaisical, looking like pushovers in comparison, and on both sides one person is looking at another in their group with a sweet longing recognizable in any teenage crush. The psychological and sexual overtones in the painting make it clear that there is a singular creativity at work, and looks ahead to the decades to come.

Degas: At the Track, On the Stage will run through February at the Art Institute.

Images from Book 360, the London Daily Telegraph, Wikiart, and Wikipedia.