Celebrated personages have been dropping like flies lately, from that Oscar-winning savior of airplanes George Kennedy to Sir Ken Adam, the man who designed the greatest James Bond sets and a war room made for fighting. As friend of the Recorder Fred Pelzer tweeted at me, “We’re hitting peak baby boomers. It’s going to be this way for the next while.”

Two deaths in the past week especially stood out to me as the product of being raised on the rock ‘n’ roll my parents and my uncles. Sir George Martin, born in 1926, and Keith Emerson, born in 1944, were two musical figures who could both be considered the smartest guys in the room: they were men of technical brilliance and great creativity that outshone many. They used their gifts in very different and rewarding ways.

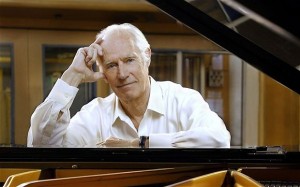

George Martin: The True Fifth Beatle

George Martin was a classically-trained pianist and oboist with a masterful knowledge of music theory and arranging. Becoming a record producer for the Parlophone label in the 1950s only bolstered his gifts, as he worked to make classical and West End recordings and comedy albums by the likes of the Goons and Beyond the Fringe that forced him to work on an inventive sound design. Thus, the 36 year-old Martin was ready when he met the Beatles, who had no formal musical education but some of the greatest instinct and imagination of all time.

George Martin was a classically-trained pianist and oboist with a masterful knowledge of music theory and arranging. Becoming a record producer for the Parlophone label in the 1950s only bolstered his gifts, as he worked to make classical and West End recordings and comedy albums by the likes of the Goons and Beyond the Fringe that forced him to work on an inventive sound design. Thus, the 36 year-old Martin was ready when he met the Beatles, who had no formal musical education but some of the greatest instinct and imagination of all time.

Martin’s partnership with the Beatles is an instructive lesson for any artist. Only once, at the beginning, did he overrule their wishes: thinking Ringo Starr was not up to professional standards, Martin engaged Andy White to play drums on their first single, “Love Me Do”/”P. S. I Love You” and relegated Ringo to handheld percussion. He quickly realized that the band as a unit was superior, especially in recording their magnificent debut album Please Please Me, recorded in a single day to recreate the energetic style of their Liverpool and Hamburg concerts. In the first sign of the band’s trust in Martin, they took his advice to speed up the title track, which had been a ballad, and they earned their first chart-topper.

Martin’s meticulous work ethic and supportive personality led first to the golden classics of Beatlemania, then the unparalleled recordings of the mid-to-late sixties, when Martin helped the Beatles realize every idea they had. He famously urged Paul McCartney to record “Yesterday” with a string quartet, and in turn worked an unprecedented bit of recording mastery with his able engineer Geoff Emerick to, in the days before digital mixing, fuse two vastly different takes of “Strawberry Fields Forever” into one of the most unforgettable pop songs. It is also fair to say that Martin’s presence as arranger, conductor, keyboardist, and willing fellow experimenter made Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band what it became.

My favorite story about the Beatles and Martin’s relationship is this: Martin was as fed up with the band as they were with each other during the difficult sessions for The Beatles and what became Let It Be. By February 1969, the band knew they were on their last legs but wanted to end things on a good note. McCartney humbly went to Martin and asked if they could make a final album together “the way we used to do it.” Martin sternly replied “Only if you promise you will be the way you used to be.” “We promise,” McCartney said. The result, Abbey Road, was one of their most extraordinary achievements. It is also a record that sounds like no other album I have heard before or since. Prosaically, Martin produced the LP on eight-track with what Emerick, quoted on Wikipedia, described as a system with individual limiters and compressors on each track, allowing for an evened mix that produced sounds of unnatural clarity, but emotionally, Abbey Road has always to this writers had a sound whose production and qualities cannot be described with words but only with feelings. It sounds like bitterness, experience, wry humor, and overwhelming love captured in concrete form.

My favorite story about the Beatles and Martin’s relationship is this: Martin was as fed up with the band as they were with each other during the difficult sessions for The Beatles and what became Let It Be. By February 1969, the band knew they were on their last legs but wanted to end things on a good note. McCartney humbly went to Martin and asked if they could make a final album together “the way we used to do it.” Martin sternly replied “Only if you promise you will be the way you used to be.” “We promise,” McCartney said. The result, Abbey Road, was one of their most extraordinary achievements. It is also a record that sounds like no other album I have heard before or since. Prosaically, Martin produced the LP on eight-track with what Emerick, quoted on Wikipedia, described as a system with individual limiters and compressors on each track, allowing for an evened mix that produced sounds of unnatural clarity, but emotionally, Abbey Road has always to this writers had a sound whose production and qualities cannot be described with words but only with feelings. It sounds like bitterness, experience, wry humor, and overwhelming love captured in concrete form.

Martin knew that there would never be another Beatles, and he wisely spent his ensuing decades working with a wide variety of musicians, although he famously collaborated with McCartney on several occasions, the Live and Let Die soundtrack the most memorable. He helped make great singles and albums with jazz musician Paul Winter, Jeff Beck at the peak of his instrumental period, and folk-rock singer-songwriters America and Jimmy Webb. Several giants of record production and mixing, including Glyn Johns, Chris Thomas, and Alan Parsons, served their apprenticeship under Martin.

However, Martin knew what he would go down in history for, and the love he and the Beatles had for each other was mutual. Martin ended his musical career with In My Life, which mixed a new recording of his Yellow Submarine score with reinterpretations of Beatles classics by the likes of Robin Williams, Celine Dion, Jim Carrey, and Sean Connery. It is an unusual but surprisingly lovely farewell which puts Martin’s production genius in the spotlight.

(It still kills me that he was musical supervisor on the Sgt. Pepper movie, but we all make mistakes.)

Keith Emerson: You Can Never Have Too Many Keyboards

If George Martin used his talents to be the unseen figure in the background helping everything get done, Keith Emerson used his to seize the spotlight and throttle it. Emerson could, and did, play every keyboard under the sun, starting with the Hammond organ (the company would induct him into their hall of fame) and working through synthesizers, pipe organs, clavinets, and the grand piano that featured in the concerto he wrote for Works Vol. 1. At Emerson, Lake, and Palmer concerts, he would play upside-down organs and synthesizers that gave off smoke, throw daggers at his keyboards, and fly through the air on a grand piano.

For all of Emerson’s grandiosity and showmanship, he was also a great and forward-thinking musician. His first band The Nice, which began as the backing group for soul singer P. P. Arnold, helped launch progressive rock as a genre with albums such as The Thoughts of Emerlist Davejack. Then he teamed up with King Crimson’s Greg Lake and Atomic Rooster’s Carl Palmer to form the eponymous trio who mixed classical music, Jimi Hendrix loudness, improvisation, and nonsensical lyrics into a surprisingly winning formula. For a few years, Emerson, Lake, and Palmer recorded outstanding music, and their self-titled first album, Tarkus (a record telling the story of a battle between a robot armadillo and a beast called the Manticore), and Pictures at an Exhibition (forty minutes of rocked-up Mussorgsky and Tchaikovsky) secured them a spot in rock history. The dominant feature of these records is Emerson’s keyboard playing: energetic, driving, sometimes lovely, sometimes highly pretentious, and always in the best of spirits.

Soon, however, the excesses of ELP began outstripping their abilities: Brain Salad Surgery was their most successful album, but the really fun four minutes of “Karn Evil #9” that get played on the radio pall amidst the entire song’s thirty-minute running time. Following this with a triple live album and a double album mixing the piano concerto and terrible experimental pieces (with “Fanfare for the Common Man” providing the one solid relief) as punk rock dawned was a death knell. Emerson continued to compose and perform, and had several ELP reunions. His body of work deserves rediscovery more than ever, because for all the flaws of his style and substance, music was his life. This was proved by his death: he committed suicide at 71 because a degenerative disease was robbing his ability to play. He should be remembered not for that tragic ending but for the exuberance of ELP at their best.

Photos from NPR, All About Jazz, the Telegraph, the Guardian, and Entertainment Weekly