After the first woman he ever loved broke his heart, Jep Gambardella wrote a novel called The Human Apparatus. It won major literary prizes and everyone alive in Italy seemed to have read it and been inspired by it. Jep then moved to Rome, became a journalist and an even bigger celebrity, and never wrote another word of fiction. Now he’s just turned 65. His two best friends are a playwright lusting after a college girl and the foul-mouthed dwarf woman who edits his newspaper. He interviews performance artists who shave their pubic hair into Communist symbols and run headfirst into aqueducts. His upstairs neighbor in their apartment complex across the street from the Colosseum intrigues him. He’s unexpectedly connecting with a 42 year-old stripper. And everyone around him is starting to die. Not in a supernatural or murder mystery sense, but simply from aging, decaying, leaving only traces behind.

Paolo Sorrentino’s magnificent The Great Beauty is a film full of dichotomies, and here is the key one…

Like the protagonists of Federico Fellini’s similar masterpieces La Dolce Vita and 8 1/2, Jep is fully alive, fully aware and stumbling towards just possibly finding the meaning of life. But while Marcello Mastroianni in the Fellini pictures was young, explosive, and surrounded by things bursting with energy…

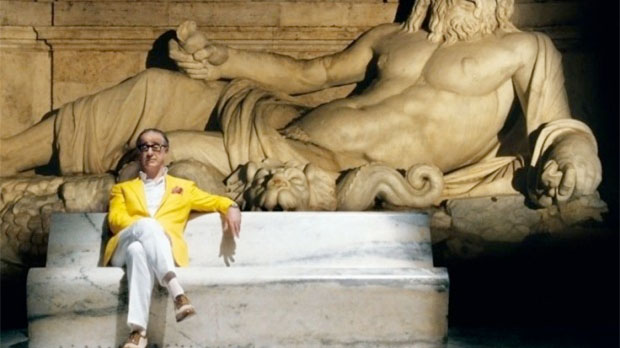

Jep is an aging man, still handsome (and actor Toni Servillo exudes the same type of charm as Mastroianni and Cary Grant), still good in bed, but more prepared to be a flaneur, an observer, than to make a giant footprint in a world that’s gone far beyond the surreal aesthetics of the sixties, a world where all recognizable touchstones are fading away and everything is instantaneous, living only for a moment, from putting up a selfie on Facebook to creating works of art worth millions of dollars.

Jep is one of the masters of ceremony for this life, but while he finds pleasure, opportunities for his dry wit, and occasional sex, he is drawn more and more to things that last and endure even when they’ve been reduced to specters. In his opening monologue, he says that even as a child, when asked what he liked most in life, he would say “the smell of old people’s houses” while all his friends said “pussy.” And thus for all his socialite status, he continually is drawn to the old churches, the longest-running of the brothels, the Piazza Navona, and in one magical sequence a candlelit stroll through one of those magnificent palaces with a key for every door, populated by decrepit nobility playing at cards.

Said nobility, the faded remnants of an imperial past, are just one of many examples of death haunting Jep at every turn. He thinks his best talents are dead, and they possibly are. His friends see their dreams and lifestyles die, sometimes shot down by Jep’s incurable honesty. (Jep really is the man Nick Carraway thinks he is.) He comforts mourners and attends funerals, all of which are presented with no warning or no explanation but are simply natural happenings in the course of existence, a reminder that death and loss are always around us. And the most vivid picture in his mind’s eye is of the Mediterranean, of cliffs, of the enigmatic Elisa who got away.

Yet from the very beginning Sorrentino introduces a motif, seemingly at first another example of faded grandeur, which grows in importance throughout the film and in the culmination gives Jep the revelation he has long sought…but how this works is something for the viewer to savor.

Sorrentino’s direction, matched with Luca Bigazzi’s flowing cinematography and the realistic yet appropriately lush production design of Stefania Cella, creates a beautiful atmosphere of Rome at once old and new, marred by the sex, finance, and morality of the Berlusconi reign but still eternal, gliding from bright lights into darkness through which colors can shine through. The fantastic soundtrack further reflects the tensions of the movie, as Lele Marchitelli’s original music glides in and out with modern classical, Europop, and post-rock (Rachel’s “Water From the Same Source” being a special highlight).

But while the images and sounds of The Great Beauty will stay with one for a long, long while, I believe the themes will resonate even longer, perhaps to the grave. My parents are approaching 65, and I could hear them speaking through the suave, measured, but romantic and yearning tones of Jep Gambardella, of seeing things come to an end, of making sense of a world that’s always changing, of making the time to do only the things you want to do, and of being aware that the last chapter of your story may not yet be written, aware that there may be something so important out there which you’d never thought of before.

This optimism, never so fully expressed in the works of the great Italian directors of the fifties and sixties, combines with the country’s singular penchant for mixing the real and the whimsical to create a moving piece of pure cinema. I would go so far as to rank The Great Beauty with 12 Years a Slave and Gravity as the best pictures of the year…it deserves rewatching, lingering over details, and will age like the finest Sangiovese.