Normally, I write about movies and baseball here on the Recorder. More often than not, these two fields exist independently of each other. (Side-note: after all these years, I still misspell independent from time to time. Just thought I’d share, none of us are perfect.) On rare occasions, these fields intersect.

(For the record, I’ve still yet to see Million Dollar Arm, which seemed to showcase a little too much racism for comical intent in its previews for me to really want to sink my teeth in. I’m also still behind the curve – so to speak – on seeing Moneyball and 42. Sue me.)

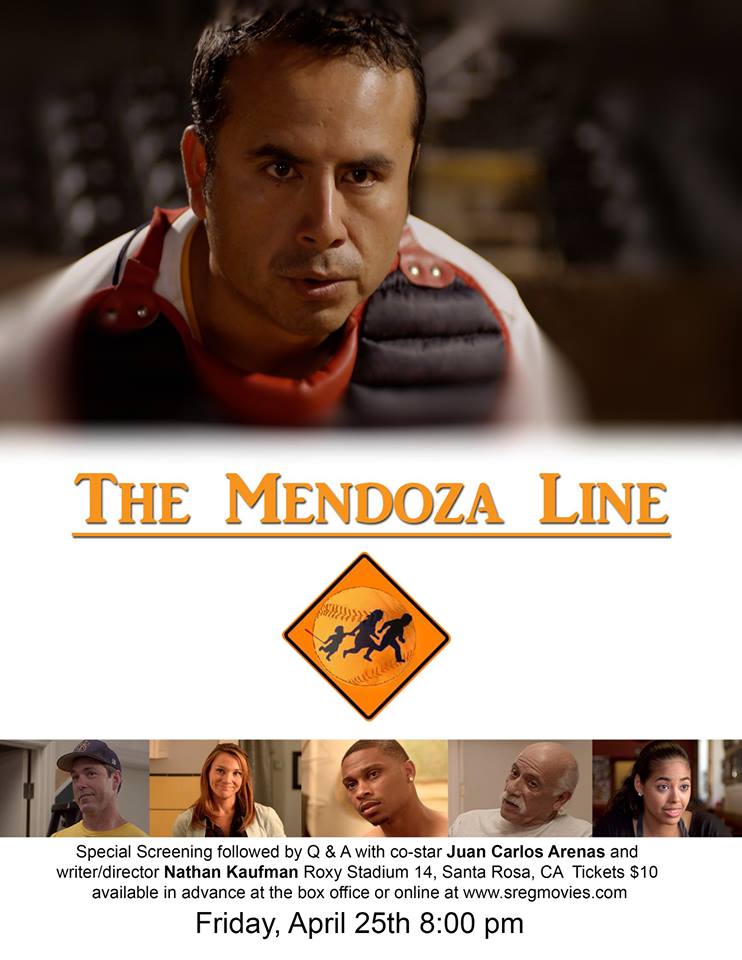

As a member of the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America, it is occasionally my pleasure to survey the work of other members. Usually, that’s in written form. (See my review of John Rosengren’s latest book here) On this occasion, I was privileged to be invited to screen writer/director Nathan Kaufman’s independent feature film The Mendoza Line. By screened, I mean set up with a laptop in a certain chain coffee shop across the street from Wrigley Field. (Nathan, if you’re reading this, you might be happy to note that I tilted my laptop towards that most hallowed of stadiums, so that Wrigley got to see a piece of your movie. Unfortunately, the Cubs are in San Diego, so no thoughts from Anthony Rizzo will be found here. I tried, man. I tried.)

The Mendoza Line deals with the struggle of Ricardo Perez (Juan Carlos Arena) to simply stay above water as a back-up catcher for the Single A Marysville Gold Sox. Ricardo is an illegal immigrant from the Dominican Republic, that hotbed of baseball that has produced such stars as Juan Marichal, Pedro Martinez, and David Ortiz. However, Ricardo’s skills are not quite up to the stature of those legends – he resents being labeled an “organizational player”, the signature of a prospect who has failed to pan out, always at risk of being dumped for the latest big thing. Ricardo and his wife, Christina (Valentina Lugo), have spent four long, trying summers waiting for his baseball dreams to come to fruition, watching as one player after another passes him by.

Immediate comparisons might arise to Bull Durham, the legendary Kevin Costner comedy about love and sex in the minor leagues, but the focus of those two movies could not be more different. Bull Durham is more concerned about the dreams of stardom. In The Mendoza Line, Ricardo is simply trying to stay above water.

“The Mendoza Line” is a baseball term used to refer to a player who is struggling to hit .200, the lowest standard of baseball hitting mediocrity. Named after former Mariners shortstop Mario Mendoza (he of the lifetime .230 average), it is applied to anyone who is in immediate danger of washing out entirely of the big leagues, something that Ricardo flirts with throughout the entire movie as he battles a protracted slump. The Gold Sox are a team filled with players who seem to display little to no passion for the game – and who can afford to? We see two players let go throughout the film, the first given his outright release, and the second released after injury prevents him from pitching. Here, there is no time for Bull Durham’s idolatry of “the show”. Here, everyone is simply trying to tread water, to stay above the line.

Throughout the film, we see the different ways that this wears on Ricardo. He becomes disgusted when he discovers a friend on a rival team using steroids in order to try and get ahead – it would be so easy to have Ricardo take advantage of “an undetectable drug” to try and move up through the ranks, but Kaufman wisely avoids using what might become a clichéd trope. His marriage to Christine struggles, as both are out of the house for long hours trying to support their fledgling family. Arena gives a restrained performance, avoiding the acting pitfall of raging out at everything, and instead showing the nuance of four years of wear and tear on Ricardo’s hopes and dreams. As his false social security number becomes widespread knowledge on the club, Ricardo comes close to breaking. “How can you live life knowing that at any given time, everything you’ve got can be taken away?” he asks as the pressures of existence begin to mount. The Mendoza Line is deeply interested in exploring what happens to men who are starting to realize their limitations and that their dreams might be just beyond them, just out of reach.

Much is made of the cultural divide between America and Ricardo’s native Dominican Republic. The opening montage of coffee bean workers and Dominican hills, set to a mariachi-infused rendition of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land”, portrays the humble beginnings of countless youths who dream of nothing more than growing up to reach the major leagues of professional baseball. By contrast, Marysville is portrayed as a sleepy American town. Countless signs advertise support for the NRA. A Wal-Mart truck drives by. At one point, Ricardo is forced by the team to hock coupons for upcoming games at a small, Mexican diner. This is Anytown, USA, a place where the American Dream struggles to survive.

The Mendoza Line further explores the theme of “a dream deferred” through the team’s manager, Phil Pichette (Lon Sierra), a one time prospect who labored for ten years in the minors before blowing out his elbow. Reduced to managing for the hapless Gold Sox, we are continually shown Phil struggling to keep his own marriage afloat, burdened by countless years of no summer vacations, long nights apart, and certain rules that preclude a happy, normal existence. Phil spends much of the movie reading Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, another allusion to the hardships that come not from trying to achieve your dreams, but simply trying to get by. Very few characters in the film can be said to be living out their dreams – most are giving their most valiant efforts just to try and stay above “the Mendoza Line”.

Shout-outs must be given to the actors, and to Kaufman’s script. While somewhat burdened by exposition at times, he blends the baseball action with the human drama with a sharp editorial eye. Every character here has been somewhat jaded by life – in fact, the only ones free of any shattered illusions about life seem to be children. We see one girl come up to the team, boasting about her baseball team’s triple play. At another point, we see Ricardo stop to coach a young boy on his swing, leaving him with a glove full of baseballs. The film isn’t trying to say that dreams are for children – rather, I think, it is saying that without children to dream, there would be no hope for us in the future.

Kaufman concludes the film somewhat unexpectedly, giving it a fairly ambiguous ending. I won’t spoil anything here, but it’s fairly safe to say that as the film progresses, Ricardo comes to learn what truly matters to him in life.

As with many independent productions, you won’t find The Mendoza Line in a theatre near you. (The latest iteration of Spider-Man has taken up too many multiplex screens for that to happen.) However, access is easy enough, and if you’re a devoted baseball fan, I highly recommend seeking this out on Vimeo, where it can be rented for a relatively cheap $3.99 (or purchased for $9.99). The link can be found here. I also highly recommend it to lovers of independent cinema, to those struggling to get by, or for those intrigued about what happens when the dream deferred threatens to explode in our faces. If nothing else, The Mendoza Line is a reminder that, although dreams may not always turn out the way we want them to, the journey to achieve them often is more rewarding than the dream itself.