This weekend marks the return of a cultural touchstone of our generation.

What? Yes, I know there’s a lot of vague, loaded terms in that grand declaration. “Generation” itself could spawn an entire graduate curriculum based around its vaguaries, as could trying to figure out what the hell a “cultural touchstone” is, anyway.

But you know what? We stand by our opening line. Because this weekend is when the new season of The Venture Bros. starts on Adult Swim.

At last!

If you haven’t had the illuminating pleasure of watching The Venture Bros…. We are deeply sorry for that hole in your life. On its surface, it’s a cartoon, a comedic re-imagining of Hardy Boys or Johnny Quest for the modern day. But the reason the Ventures have such a dedicated fanbase is that the series is so much beyond the surface: it’s an emotionally-gripping look at flawed and yet hopeful characters. It turns an electron microscope onto failure, expectations, disappointment, American exceptionalism, absurdity, and what superheroes & super science looks like when faced with accountants and bureacracy.

Oh, and it’s riotously funny in unexpected and creative ways.

-J.:

Okay, where to start this conversation? It’s tough, because there are so many jumping-off points. I mean, take a look at the Journal of Venture Studies – so many topics we could discuss. Hrm. Let’s see… might as well start general, with one of the broad strengths of this series: character development.

On the grand scale, the way the writers have developed the characters in this series is almost unparalleled. At the heart of the overarching narrative are the expectations of parents passed down to their children. The titular characters are Hank and Dean Venture, teeange sons of Dr. Thaddeus “Rusty” Venture. Rusty is the son of America’s greatest scientist & exemplars of our country’s exceptionalism in the post-WWII era, Dr. Jonas Venture. Rusty was also a popular boy adventurer who had his own Saturday-morning cartoon.

At the outset of the series, the impression is that Rusty Venture is not a great person, as well an awful father to his two naive boys. Jonas Venture, by contrast, appears at first glance to be a Great Person and an ideal father. But as we learn more and more about the characters and their history, we learn that surface impressions are just that: surface. Jonas looked at fatherhood more like a biological consequence than a relationship. Below the glittering shell of being a Great Person, Jonas was the antithesis of a great father. In comparison, Rusty’s seeming apathy towards his boys appears a much more merciful approach towards fatherhood.

(As an example, one episode follows a day where Rusty is possessed by an enemy, and almost forced into suicide. After surviving the insane ordeal, another character worries about Rusty’s mental health. Rusty laughs, and recounts a painfully emascualting & nightmarish 16th birthday party thrown by his father. He compares the two events thusly: “Oh, no! No! What I went through today was ‘like a nightmare.’ What happened when I was 16, that is my LIFE.”)

Venture Bros. excels at turning character expectations on their figurative heads. During last season, for example, the character of Professor Impossible turns to villainy. The Professor is this show’s parody of the Marvel superhero, Mr. Fantastic – a brilliant scientist and archtypical good-guy superhero. The comedy of the situation is watching a do-gooder suck at trying to “be evil.”

You can tell he’s turned evil: look at that eye makeup! And that pipe!

The show then turns on our expectations, when it’s revealed how Professor Impossible powers his impressive headquarters. It is morally repugnant, ethically revolting, and unerringly evil. But because it’s also a logical & scientifically sound solution to a problem, the Professor doesn’t even give it a second thought (morally). In fact, he was one of the world’s greatest “good guys” when he came up with it. Because success, science, and the greater good were more important than consideration for another human being, Professor Impossible doesn’t see the evil inherent in his solution. While he flounders at being a “bad guy,” he succeeds at being unintentionally more evil than a life-long villain.

What about you, Alex? What excites you about this show?

ALEX:

As much as I adore The Venture Brothers, and I do, our opening line might overstate things just a bit. It’s a show that will probably always be a bit too weird and specific to become a cultural touchstone. Among those who know and love it Venture is a big damn deal, and that might be indicative of a generational thing (folks our age seem much happier to let their nerd flag fly), but it’s still a show that I think most people might have seen an episode or two of and not much more. But you know what, J.? That’s awesome. The Venture Brothers is a perfect is a perfect example of a cult show and I am more than happy to be part of the cult.

I think you hit on some good points in regards to the way Doc Hammer and Jackson Publick (the Venture showrunners/ writers/ voice-

What makes this grand ensemble really sing, for me at least, is how much the world around them has been built out too. The Venture Brothers takes place in a world that seems just like ours — except for the not-insignificant presence of world-famous Super Scientists, an Arch-Villains’ union, extra-legal spy agencies in the sky, and necromancers living next door. If all of that sounds bizarre and inexplicable, well… it sort of is unless you watch the series through from the start (hence the cult status). But for those with the right mixture of nerdery and fortitude I think the fictional world of The Venture Brothers is as wonderful and encompassing as any other.

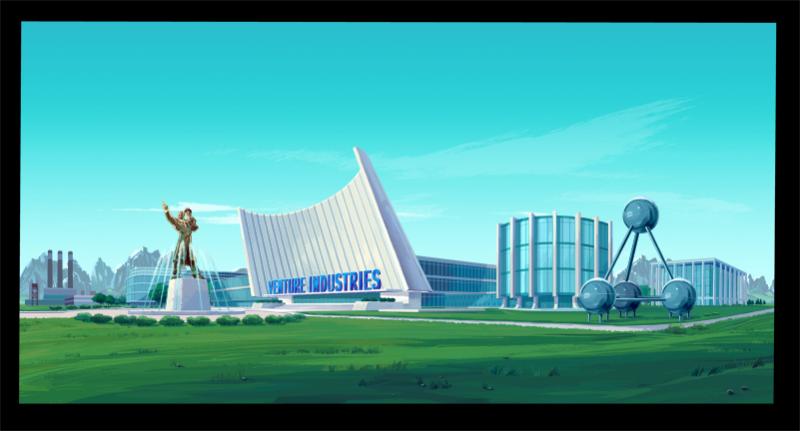

The shabbily faded mid-century grandeur of the Venture compound and the strange, sad tradition of underground trivia bowls are but two small elements of the show’s universe that seem as lively as a government office in Pawnee or a co-ed loft in Los Angeles. It’s a world tinged all over by failure and regret; Hammer and Publick have said that failure is the unifying theme of their show, but I think that only aids its charms. This is a world that only seems to accept those who have been knocked around by life, which makes their small triumphs and frequent flailings all the more affecting.

I think that ties in to some thoughts you had on the show’s emotional affects, -J.?

-J.:

What?! ME? OVERSTATE?

Preposterous.

Though you might be a wee bit more accurate when describing The Venture Bros. as a cult show rather than cultural touchstone. Then again, Rocky Horror Picture Show managed to achieve both, so here’s to hoping the Ventures do the same.

And the comparison to Rocky Horror might be rather illuminating, in terms of fans and their die-hard love of the series. The show has spanned a full decade, even though it’s only up to Season 5. This means that it catches the tail-end of the Gen X crowd, who grew up on Hanna-Barbara, moved into the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and bemoamed the short-lived nature of The Tick. But it also is squarely in the middle of the Millennial generation, who aren’t afraid to let their nerd-flag fly, as you said. This is also the generation that is watching the Space Age expecations of the Baby Boomers turn into the failed promises and hollow disappointment of the current age, a common trope that is central to The Venture Bros.

Let’s go back to The Tick for a second, because I think that’s another great element of the backstory here. For all its glorious parody, The Tick had difficulty sticking around. It had a brief comic-book stint in the early ’90s. It had a well-loved animated TV show later that decade, but only ran for three seasons. And then there was the live-action TV series in 2001, which lasted a half-season. The combination of absurd parody and hilariously silly quotes didn’t allow for much character growth — or, at least, it wasn’t given much opportunity to develop such growth.

From the ashes of the live-action Tick came the phoenix that was Venture Bros. Chris McColluch, a writer for The Tick, would re-christen himself as “Jackson Publick” and team up with one Doc Hammer. He knew an actor named Patrick Warburton, who had played the live-action Tick, and got him to sign on as another bigger-than-life character — Venture family bodyguard Brock Samson. (Warburton was a common reason for why a lot of initial fans — including this one — gave the series a shot.)

Nice ass, Samson

You’re right about the first season, Alex. I don’t know if I’d call it “dry,” but it was much more in the parodic vein of The Tick, only parodying Hanna-Barbara instead of superheroes. And you’ve also nailed the moment it started to turn into something more. The first season was funny, but it didn’t make you really stand up and notice until the finale. Not only did a couple of bumbling henchmen accidentally kill the Venture brothers, but Dr. Venture “gives birth” to a twin brother that seems to embody everything he was not. But there would be a season two. Season Two?! How? The titular characters are dead! They even had a cheesy ballad playing during the denouement of their shuffling off this mortal coil!

It was with the start of season two that the writers really began to develop Venture Bros. as a complex, mature show. Two years after the Venture brothers died, a huge group of us gathered to see just how the show would bring them back. What had once been a silly show now had us caring about more than jokes. The second season moved The Venture Bros. to be less of a parody, and more of a pastiche. Characters were allowed to develop, joking references became important plot points, and the writers molded the narrative so that the audience could emotionally invest in the characters.

“Doctor Henry Killinger. And this is my Magic Murder Bag.”

A good example of this is Dr. Killinger, an obvious riff on the real-life diplomat & politician, Dr. Henry Kissinger. But the character goes beyond mere reference. He’s a villain who almost seems to do, well, good. He reunites a pair of supervillains in love. He fails to reunite the Ventures with an old bodyguard, but at least saves the boys’ lives. He also completely reinvigorates Venture Industries, elevating Rusty Venture to become a better man, a Great Man — assuming Dr. Venture is okay with becoming a villain. In Killinger is the Devil, but also the realization that sometimes being the best you can be means sacrificing ideals… and is the elevation worth the cost?

It’s these nuances and narratives that allow the audience a chance to emotionally connect with The Venture Bros. I’ll flat-out admit it: I’ve cheered during episodes as loud as I have during sporting events. When Henchman 21 throws down with Brock Samson, bringing his character arc full circle? I pumped my fist and cheered. During the “Murderflies” speech before the showdown at Cremation Creek? I was pumped and ready to fight. When a bodyguard hints at the fate of Jonas Venture, or right before Hank’s mindwipe in “Everybody Comes to Hank’s“? Stunned, surprised, and amazed.

“Don’t bother saying you’re sorry…”

Then there was the climax of last season’s finale, where long-simmering tensions both personal (Dean’s unrequited love, 21’s uncertain path forward, Brock and Molotov’s relationship) and international (espionage, a comatose villain, and a hover-headquarters) come to their head. All the while, the sounds of Pulp‘s “Like a Friend” punctuates the tempo of the narrative, underscoring the repetition, failure, disappointment, and longing that have lead to this need for catharsis. The guitar kicks up, and the singer begins to admonish himself in earnest for his weakness (“You are the last drink I never should drunk / You are the body hidden in the trunk”), and we watch Brock Samson give everything he’s got to save a flawed family that isn’t even his…

Yeah, I was standing and yelling when I first watched that scene. I still get goosebumps every time I see it again. And, in typical Venture fashion, the writers tilted our expectations — out of failure and poor choices comes happiness, and I was smiling as wide as Brock was when last season ended.

Now, the Venture Bros. and its world, its characters, and its tales return for another season. Cultural touchstone? Maybe it’s an exaggeration. But there are so few TV shows that can weave an sustain such a quality narritave, much less while keeping true to its roots in comedy and science fiction.

Go Team Venture!