FEAR THE BEARD

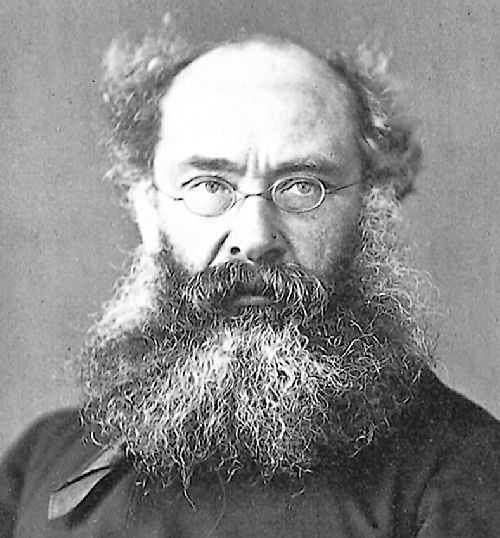

The older I get and the more life experience I obtain, the more life imitates art…in rare cases the stories I imagine telling come true (more on that fifty years from now or when some of the principals are dead), but more specifically I see the ideas, hopes, and fears of past generations manifest in our reality. Above all, the work of Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) seems to be the most prescient.

I should add a disclaimer: I love Trollope more than any other novelist, even though my all-time top ten wouldn’t include a single of his books. Maybe not even my top twenty. Yet two shelves are filled with nothing but his work, I wrote my master’s thesis on him, and I accumulated enough research to plan multiple doctoral projects during the stretch in 2011-12, right before the Recorder’s founding, when I was planning on becoming a professor. What fascinates me about Trollope is how, under the cover of so many three-volume, serialized novels filled with sensation, sometimes annoying but sometimes hilarious authorial commentary, and plenty of marriages and rewarded virtue to go around, he was documenting the age he lived in and, by mixing his own philosophical notions of things into the narrative, the eternal cycle of human civilization rising, falling, and changing. This is why, in light of the government shutdown, my thoughts have turned to Trollope, for how political and social structures operate was his most obsessive, detailed theme. By this, I mean that Trollope devoted twelve novels to one ongoing narrative with continuing characters and plotlines, the six volumes of the Barchester series (published between 1855 and 1867) spinning off the six volumes of the Palliser series (1864-1880). In these books, Trollope depicted Victorian Britain in transition.

The Barchester novels are a portrait of the old world of a firmly in control aristocracy dominated by landed, titled figures and the symbolism of the Church of England. When Trollope began the second series, based around a minor character from The Small House at Allington, he recognized that the entire population of Britain, fueled by their numbers and the free press so essential to creating public opinion, was electing a representative Parliament that probably had more claim to set national policy than the privileged few, and yet the privileged few still retained a firm grip on the nation. In looking at this conflict, Trollope’s position was one of reconciliation, and his political philosophy becomes the main undertone beneath his romances, murder trials, contested wills, and railway accidents.

Trollope set down this philosophy without ambiguity in The New Zealander, a work written in the 1850s but not published until almost a century after his death…although its concepts would appear in almost every work of fiction he ever wrote. Trollope, who had seen enough of Britain and the world and experienced comfort and poverty alike, knew that inequality was a fact of life, only this influenced him to divide all people into two main classes: the rulers and the subjects. The rulers were those fitted by birth, education, and other gentlemanly qualities (more on this last point in a bit) to wisely lead the nations. The subjects’ duty was to get the rulers into power, through democratic means preferably (Trollope encourages Parliamentary government but is so insistent on the ruling class’s power that I find it hard to imagine he would have said nay to less democratic varieties, though not so far as totalitarianism), and then to obey the rulers’ choices. Crucially, in return, the rulers were to listen to the subjects and act in ways to promote their welfare and respect their demand. In Trollope’s view, the rulers held responsibility for their subjects and this duty—which the aristocracy in his works invariably called upon as their apologia for entering politics—was paramount above all.

This philosophy seems like, to borrow a favorite Trollopian phrase, a castle in the air. It wants to have things both ways: rulers wield unquestionable power over subjects while being answerable to the subjects. Yet digging deeper into the subtleties reveals it to not be such a paradox. Trollope’s point is that a wise, educated populace of subjects formed by considered gathering of facts and opinions cannot help but choose the best rulers, and this same wisdom will guarantee that their wants and needs are just as thoughtful, plausible, and promoting the common good. This may be an ideal situation, but every political philosophy is based on some sort of idealism, and Trollope’s was injected with a firm shot of reality, as seen when his great mouthpiece, the noble, selfless, and incredibly good Plantagenet Palliser articulates this vision in the late novel The Prime Minister (which Tolstoy called a masterpiece of its kind). Palliser/Trollope is/was a self-described “advanced conservative liberal” who worked to move men and women on a path with a “tendency towards equality.” Both these phrases are worth considering. Trollope recognized that any society will necessarily change over time, and rulers need to adapt to these changes while preserving the parts of the system which work best and provide a sense of unique identity to the citizens of a nation. Similarly, Trollope knew that human nature made complete equality a fantasy, except in dictatorships or Communist societies where equality was achieved by coercion. He believed in free thought and action, and knew that such self-determination leads to some having more advantages than others, but also a thoughtful, logical society could legislate and rule itself in a way which reduced the most blatant mechanisms producing inequality, could ensure that all people had the same basic rights and opportunities. This state of affairs is not a castle in the air at all, but something very possible.

Which is why, as the title claims, Anthony Trollope would bring John Boehner to heel. Under his philosophy, the Tea Party faction of the Republicans breaks so many of his cardinal rules, two most crucially. It refuses to take responsibility for the people who elected its members to Congress, preferring to cease all governmental operations and threaten the stability of the nation—including their constituents. And worse, they fly in the face of the American tradition and the parts of our government worth preserving. They are trying to coerce their minority voice into a position of power in a democratically-elected government which does not support their vision as a whole.

Yet while Trollope would be raging at Boehner, he also would not be surprised. His novels were written at a time when a prosperous Britain was divided between the Liberals and Conservatives, each with their own charismatic leader—the pious, priggish, driven William Gladstone and the charming opportunistic man of action Benjamin Disraeli—and he wrote at length about the factors which made politics and social organization so full of contention in so many far-reaching ways. His novel The Way We Live Now, which many consider his greatest stand-alone book (I find it uneven but magnificent in its ambition) alone covers a multitude of 21st-Century sins, including engineered financial crises, the purchase of political power, and the collapse of a responsible media into a money-grubbing organization more concerned with pleasing the public than with fair and honest reporting and literature. This was written in 1875. And in perhaps the best of the Palliser novels, The Eustace Diamonds, he avoids topicality and writes about themes which still sadly ring true: politicians more concerned with their image than being productive, living in a society more occupied with frivolity and sensation than with the actual doings which set the course for a common future. (All the supporting characters—the wealthy, the titled, the government officials—are focused on the actions of the protagonist and her web of death, sex, and crime while Palliser professes ignorance and carries on his economic reform.)

Trollope was not perfect. There was a touch of unthinking racism and excessive English pride in his work, and his attitude towards women was complex, to say the least. He thought women were frequently as intelligent and strong as men, if not more so, but tradition held that they should keep to a certain sphere of influence and a certain propriety of behavior, and this tension is one of the most central fascinations of his work. (That he himself was infatuated with a bisexual American feminist didn’t help matters.) But the main thrusts of his philosophy are ones which deserve our attention. There is no best of all possible worlds, for him or us, but his ideas point the way towards a sensible world. He’s rigorous, demanding, and respects the reader’s intelligence as he weaves a mixture of story and commentary. Jane Smiley called him a novelist for grown-ups, and his work backs up such a claim.

But while Anthony Trollope is a bit foreboding, he’s also immensely fun. His books often carry a great mix of intentional humor inspired by his idol Thackeray and unintentional humor for us today (he once titled a chapter “Mr. Outhouse Complains That It’s Hard” which is my favorite chapter title EVER), and his plotting is full of recognizably human characters, never entirely good or evil, in situations where the ending may not be in doubt (marriage and fortune) but how they arrive there is exciting in the reading. I’d urge anyone to give him a chance. The Barchester-Palliser works (enumerated on Wikipedia and elsewhere) are his best, but for those who want a stand-alone book, He Knew He Was Right (his ultimate chronicle of male-female dynamics) and The American Senator (a fantastic observation of the workings of money and power in society, ending with a speech in which the titular character sums up the best and worst of American and English government) are also worth the read. They’re terrific storytelling shot with Anthony Trollope’s own special voice and wisdom, and when you’re done with them, you may find your own reasons for wanting to take our government to task may have renewed vigor.